Updated on

February 19, 2026

Sounds~Write: A Teacher's Guide to Linguistic Phonics

|

February 19, 2026

Updated on

February 19, 2026

|

February 19, 2026

Sounds~Write is not another phonics scheme. It is a linguistically coherent system for teaching reading and spelling that starts with sound, not letter names. Created by John Walker and built on three decades of linguistic research, Sounds~Write places the sound as the primary unit of instruction, with written symbols (graphemes) following as the representation of those sounds. For teachers weary of phonics schemes that seem to work for some pupils but mysteriously fail for others, Sounds~Write offers a systematic alternative grounded in how language actually works.

The method sits comfortably within the Department for Education's approved Systematic Synthetic Phonics (SSP) programmes, but its linguistic foundations set it apart from competitors. Where many phonics schemes focus on letter-sound correspondences as isolated pairs, Sounds~Write teaches the alphabetic code as a coherent system where sounds relate to one another, and spelling choices reflect historical and linguistic patterns. This article explores how Sounds~Write works in practice, when it works best, and how to integrate it into your classroom.

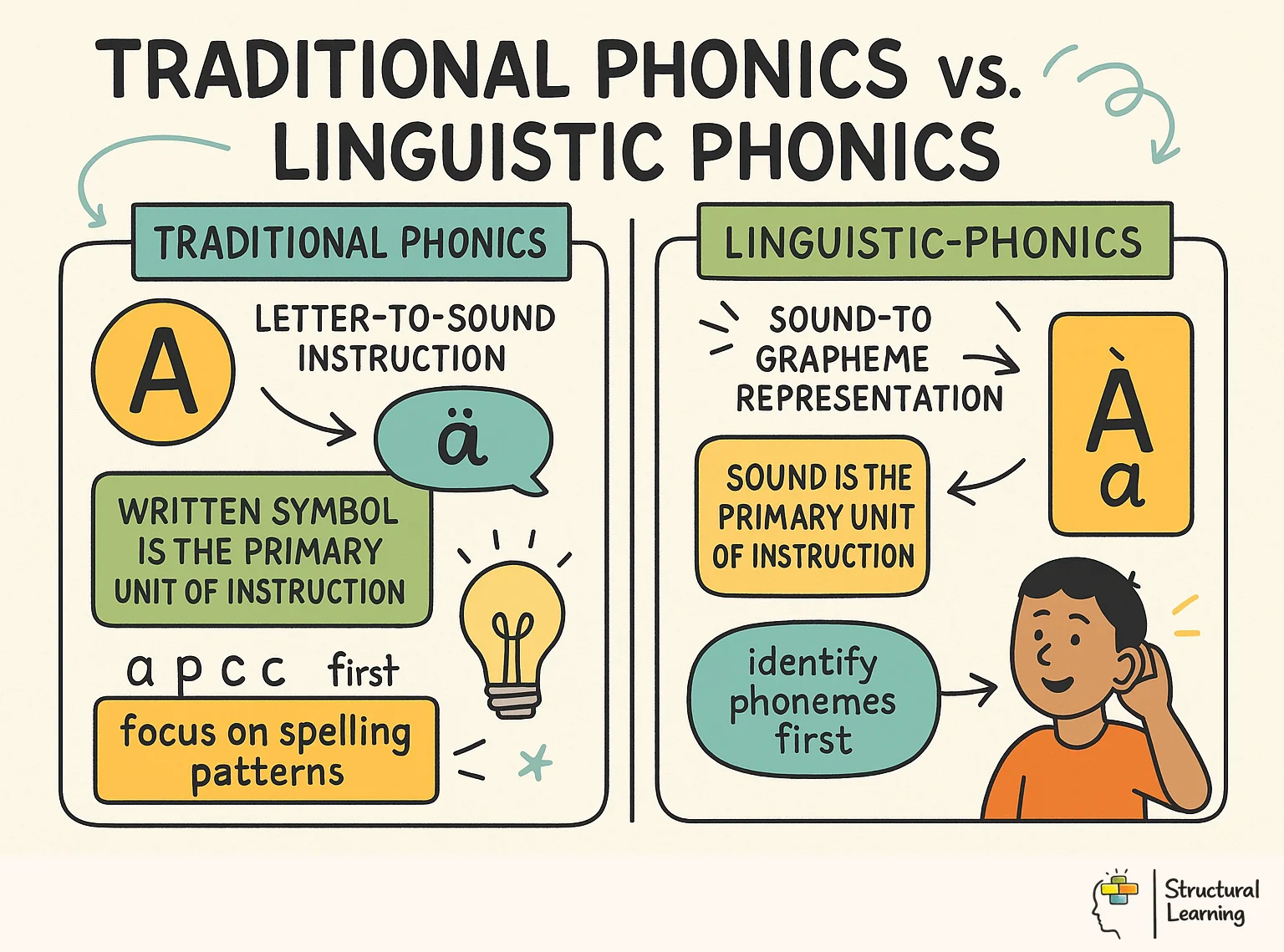

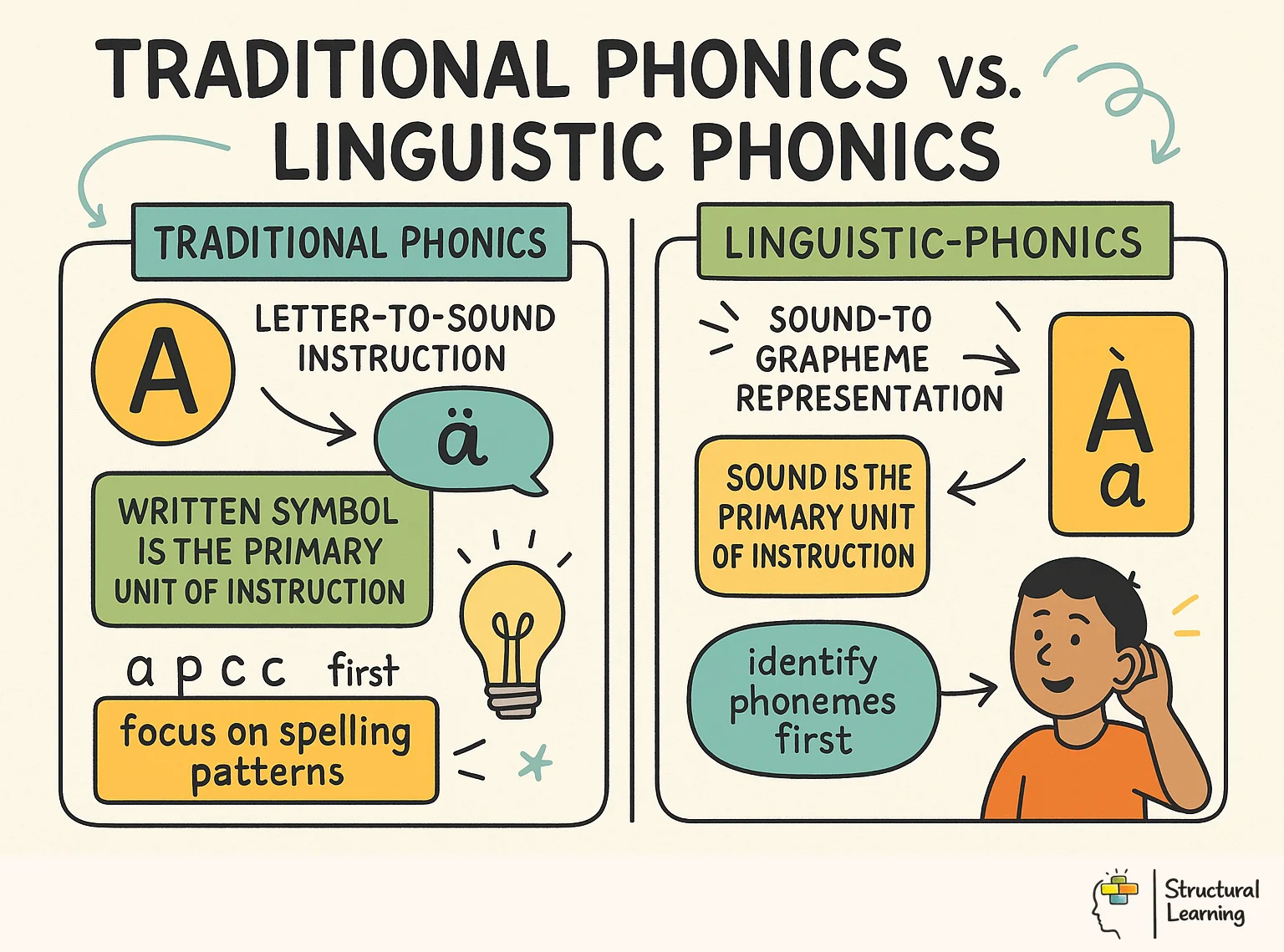

Sounds~Write is a comprehensive phonics programme designed for children aged four to eleven. It teaches pupils to read and spell by starting with the sounds of English (phonemes), then teaching the written forms (graphemes) that represent those sounds. This is the reverse of how many traditional schemes work. Traditional phonics often begins with letter names (a, b, c), then tries to connect letters to sounds. Linguistic phonics begins with sounds and works toward their written representation.

The term "linguistic phonics" reflects the programme's foundation in linguistics research, particularly the work of Diane McGuinness. McGuinness (2004) argues that phonics teaching should follow the actual structure of English orthography rather than arbitrary groupings. Where letter-name-based phonics might teach "the letter 'a' makes different sounds," linguistic phonics teaches "this speech sound [æ] is represented by the letter 'a' in words like 'cat', and by other graphemes in other contexts." This shift in framing changes what children understand about reading and spelling.

The Sounds~Write approach recognises that English is not phonetically simple, but it is systematically organised. Once you understand the linguistic principles underlying English spelling, the apparent chaos resolves into patterns. The job of a Sounds~Write teacher is not to simplify these patterns away, but to teach pupils to see them clearly. A pupil who understands that the long 'e' sound can be spelled 'ee', 'ea', 'ie', 'y' (at the end of words), or 'e' (at the end of syllables) has learnt something deeper than a child who memorises "ee" and "ea" without understanding the principles that govern when each is used.

Most phonics schemes begin with letter sounds: "This is the letter 'a'. It makes the sound /æ/." The implicit message is that letters are the primary objects, and sounds are secondary. Sounds~Write inverts this. "You hear the sound /æ/ in words like 'cat', 'back', and 'map'. We write this sound with the letter 'a' in the middle of the word, but also at the beginning of 'apple'." The sound is the primary unit; the letter is one way to represent it.

This distinction matters more than it might initially appear. When a child is taught letter names first, they often slip into viewing reading as a decoding process: sound out the letters, blend them, and hope you recognise the word. This leads to the common problem of pupils who can "blend" successfully but still cannot read. They are focused on the mechanics rather than the meaning. By contrast, when a child starts with sound, the job is to recognise which sound is present and find its written form. The child remains focused on meaning from the beginning.

Consider a Year 1 pupil meeting the word 'cat' for the first time. In a letter-led approach, the teacher might say, "This is 'c', 'a', 't'. What does it say?" In Sounds~Write, the teacher says, "You can hear three sounds in 'cat': /k/, /æ/, /t/. We write /k/ with 'c' at the start. We write /æ/ with 'a' in the middle. We write /t/ with 't' at the end." The Sounds~Write version foregrounds the sounds the pupil can already perceive in their own speech, making the link to writing clearer and less abstract.

This sound-first approach also explains Sounds~Write's strength with struggling readers. If a pupil has not yet automated the arbitrary association between a letter name and a letter sound, they are already working with a double abstraction. They must remember what the letter name is, then what sound it makes. If the teacher bypasses the letter name entirely and works with sound, the cognitive load drops immediately. This is why the programme performs well with children who have phonological awareness difficulties, SEND pupils, and EAL learners for whom letter names in English are unfamiliar.

The Sounds~Write curriculum organises English orthography into three tiers: the Simple Code, the Complex Code, and the Extended Code. This structure makes the system feel manageable rather than overwhelming.

The Simple Code covers single graphemes representing single phonemes. Pupils learn that /m/ is written 'm', /d/ is written 'd', /æ/ is written 'a', and so on. There are approximately 44 phonemes in English, but far fewer graphemes needed to represent them initially. A Year 1 class working through the Simple Code learns to read and spell simple words like 'mat', 'sit', 'dog', 'red' by combining these single letter-sound correspondences. The teaching is explicit: "Here are the sounds we can make, and here are the letters we use to write them."

The Complex Code begins when pupils have consolidated the Simple Code. It addresses situations where a single phoneme is represented by more than one grapheme, or where a single grapheme represents more than one phoneme. For example, /k/ can be written 'c' or 'k' depending on the following vowel. The phoneme /ʃ/ (as in 'sheep') is written 'sh'. The grapheme 'ough' represents different phonemes in 'tough', 'through', and 'cough'. These are not exceptions; they are predictable patterns based on English phonotactics and historical spelling conventions. Teaching them systematically rather than treating them as sight words strengthens reading resilience.

The Extended Code covers the less frequent patterns and the historical layers of English orthography. This includes silent letters, borrowed letter combinations from French and Latin, and morphological relationships (where spelling patterns reflect word meaning and relatedness rather than pure sound). For instance, understanding that 'castle' has a silent 't' becomes logical once pupils learn that 'castle' is related to 'castle' (no silent 't' in the Italian source word), but English orthography preserves the 't' from historical pronunciation. A teacher explaining this is not asking pupils to memorise arbitrary rules; the teacher is showing pupils that spelling reflects deeper language structure.

In classroom practice, this three-tier structure gives you a clear roadmap. In Year 1, you focus on the Simple Code, ensuring every pupil has rock-solid knowledge of basic letter-sound correspondences and can blend and segment three-letter consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words. In Year 2, you layer the Complex Code, teaching digraphs, trigraphs, and split vowel digraphs. By Year 3 and beyond, you are addressing the Extended Code and morphology. This prevents the chaos of teaching 'sight words', which is how many programmes handle everything beyond the basic correspondences.

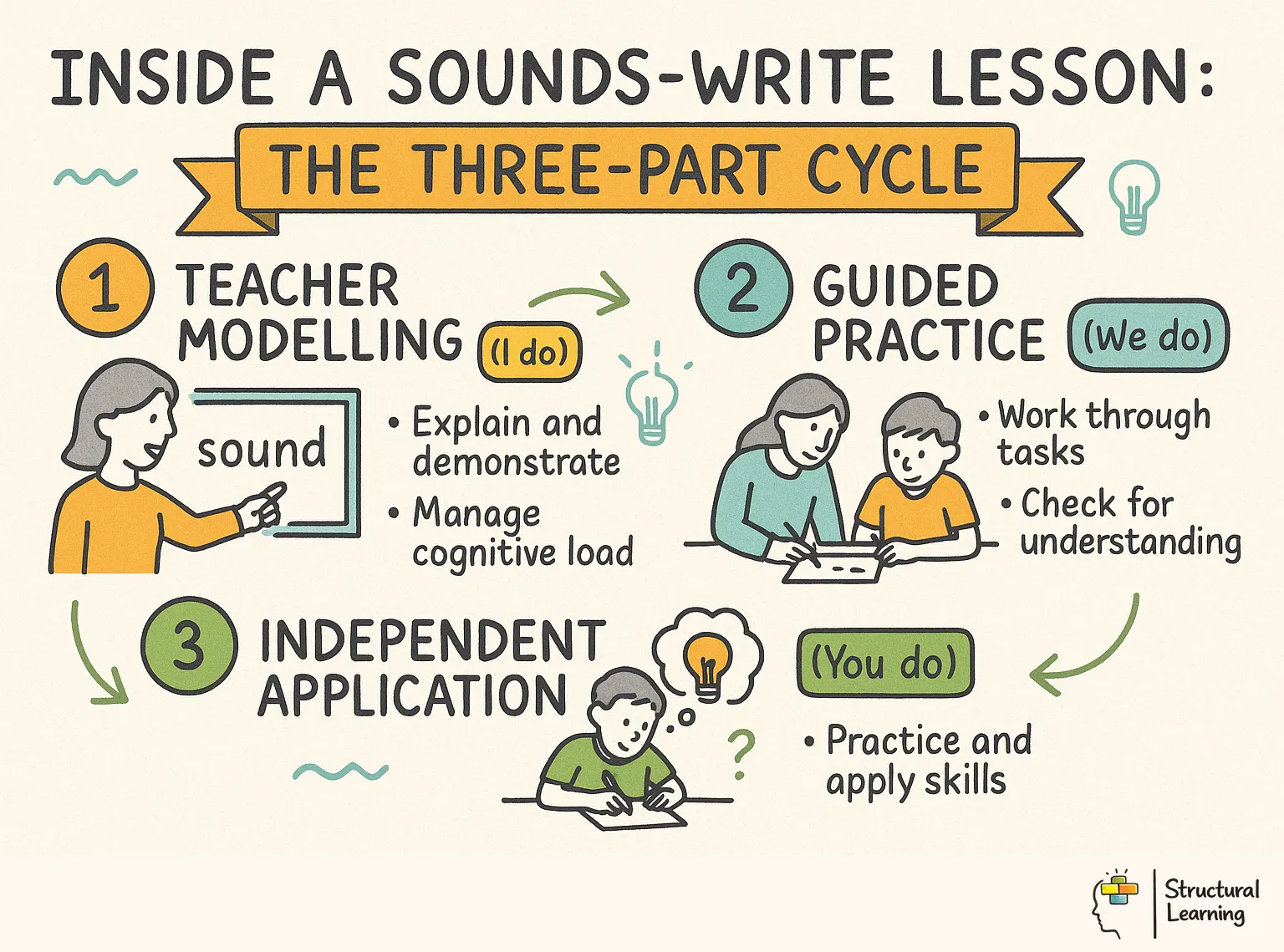

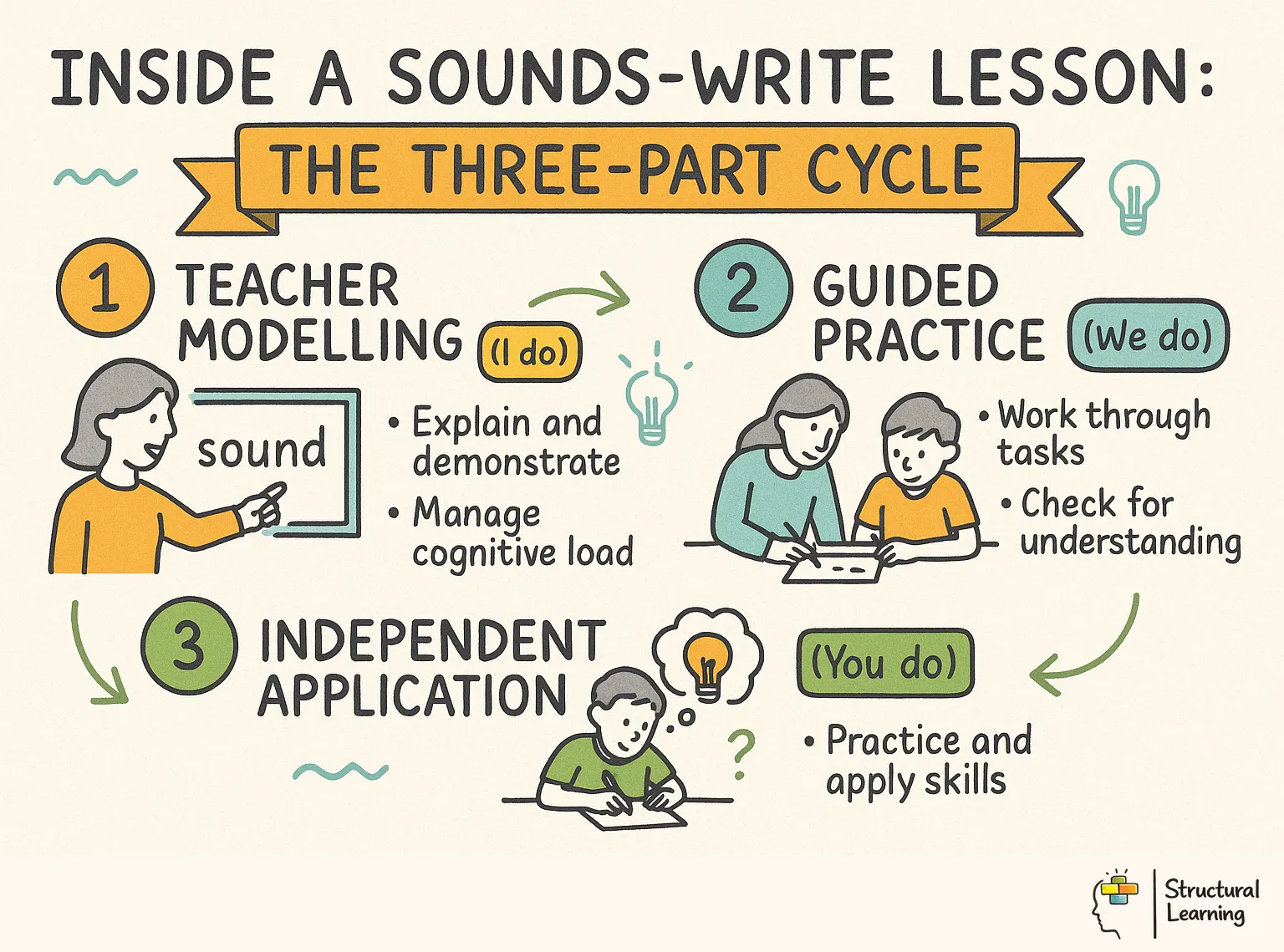

Every Sounds~Write lesson follows a consistent structure: teaching (modelling), guided practice, and independent application. This routine builds automaticity and reduces cognitive load, which is particularly important for early readers who are still developing their working memory capacity (Sweller, 1988).

The teaching phase involves explicit modelling by the teacher. If teaching the grapheme 'ai' (one of the Complex Code correspondences for the long 'a' sound), the teacher might display a card with 'ai' on it and say aloud: "I can see the grapheme 'a' and 'i'. Together they write the sound /eɪ/ as in 'rain', 'train', 'paint'." The teacher then articulates the sound clearly, links it to familiar words, and asks pupils to repeat. There is no discovery learning here; the rule is stated directly. This clarity is deliberate. The teacher is providing a direct instruction model that transfers knowledge efficiently.

The guided practice phase involves the teacher and pupils working together. The teacher might display a word like 'braid' and ask the class to identify each grapheme and say each sound aloud before blending. The teacher provides feedback immediately: if a pupil says the wrong sound, the teacher corrects it without lengthy explanation. "No, 'ai' here says /eɪ/. Let's say it together." This correction is brief and focused because the rule has already been taught. Pupils are not figuring out rules; they are applying known rules to new words.

The independent application phase involves pupils working alone or in pairs with words or sentences containing the target grapheme. This might involve matching words to pictures, completing partially written words, or writing words from dictation. The teacher circulates, observing which pupils can apply the rule and which need reteaching. This formative assessment (Dylan Wiliam's work on formative assessment emphasizes this loop) informs whether the class moves on or revisits the correspondence.

A typical Year 1 lesson might last 15-20 minutes. A teacher introducing the grapheme 'e' (saying /ɛ/) might spend 3 minutes teaching it, 5 minutes on guided practice with words like 'pen', 'leg', 'men', and 10 minutes on independent tasks. The consistency of this structure is intentional. Pupils begin to anticipate the flow, reducing anxiety and freeing cognitive resources for learning the content itself.

Sounds~Write teaches reading (decoding) and spelling (encoding) simultaneously, using the same sound knowledge. This is not unique to Sounds~Write, but the programme's explicit commitment to dual teaching is notable. When a child learns the correspondence /æ/ = 'a', they are simultaneously learning to read words with 'a' and to spell words containing /æ/. There is no delay; encoding happens from day one.

This matters because reading and spelling are not identical processes. A child might be able to read a word (recognize it from its visual form) without being able to spell it (retrieve and sequence the correct letters). Traditional instruction often treats spelling as secondary, something to tackle once reading is secure. Sounds~Write rejects this hierarchy. Spelling reveals which phonemes a child can perceive and which grapheme choices they understand. If a child writes 'kat' instead of 'cat', the teacher knows something important about the child's phonological awareness and grapheme knowledge.

In practice, every Sounds~Write lesson includes an encoding component. After pupils have practised decoding words with 'a', the teacher might ask them to write simple words from dictation: 'cat', 'sat', 'mat'. The teacher says the word slowly, pupils identify the sounds, and they write the corresponding graphemes. This encoding task serves multiple purposes. It provides retrieval practice, which strengthens memory for the correspondence. It gives the teacher diagnostic information about which pupils have confused the link between sound and symbol. It also prevents a common failure pattern: a child who can read words but cannot spell them may eventually stop reading, because they suspect they don't truly understand the code.

The linguistic principle underlying this is that orthography (spelling) directly represents phonology (sound). Therefore, to become secure in the phonological system, a child must be able to move fluidly between hearing sounds and writing symbols, and between seeing symbols and hearing sounds. Sounds~Write treats spelling not as a separate subject, but as the other half of literacy instruction.

The sequence in which Sounds~Write introduces graphemes is not arbitrary. It follows principles of phoneme frequency, phonotactic probability, and morphological productivity. This differs from schemes that might introduce letters in alphabetical order or based on the letters children already know from their names.

Sounds~Write prioritises phonemes that appear frequently in English speech, particularly in the consonants and short vowels that form the structure of most early-years words. The phoneme /m/ appears in many early words (mum, mad, mat), so 'm' is taught early. The phoneme /ŋ/ (as in 'sing') is less frequent, so it may come later. For vowels, the short vowels (/æ/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /ɒ/, /ʌ/) are taught before long vowels because CVC words with short vowels (cat, sit, dog) are more numerous in early readers.

The sequence also respects phonotactic principles. In English, some consonant clusters are common and easy to blend (bl, st, tr), while others are rare or difficult (thr before a vowel requires careful articulatory control). Sounds~Write introduces frequent clusters early and later clusters only once pupils are confident. This prevents the frustration of trying to read words with unfamiliar sound combinations before pupils have the phonological stability to manage them.

A typical Year 1 sequence in Sounds~Write might look like this: introduce 10-15 consonants (including easy clusters like 'st' and 'pl') and the five short vowels over the first two terms. Then introduce digraphs (ch, sh, th) and common long vowel correspondences (ai, ee, oa) in term three and early Year 2. This pace seems slower than many schemes, which introduce 2-3 graphemes per week. However, the Sounds~Write pace is deceptive. Each grapheme is taught thoroughly, with multiple encoding and decoding opportunities before new graphemes are added. The result is fewer pupils needing intervention or reteaching later.

Despite the systematic approach, some pupils will plateau. They may master the Simple Code but struggle when Complex Code patterns are introduced. Others may be fluent readers but poor spellers, or vice versa. Sounds~Write has embedded differentiation strategies to address these situations.

The first response to a plateau is diagnostic. Sounds~Write emphasises identifying precisely which correspondence a child has not yet secured. A child who reads 'cat' and 'mat' but cannot read 'sat' has not yet fully internalised the /s/ = 's' correspondence. The teacher's job is not to reteach the whole alphabet; it is to focus intensive practice on 's'. This targeted approach, informed by formative assessment, is far more efficient than whole-group reteaching.

If a pupil plateaus on a specific correspondence, Sounds~Write recommends breaking the learning into smaller chunks. If a child struggles with the grapheme 'ai' representing /eɪ/, the teacher might begin by teaching 'ai' in only initial-position words (aim, air, aid), where the child can focus on the new grapheme combination. Only once the child is confident with these words would the teacher introduce 'ai' in final position (wait, brain) or in complex consonant clusters (train, drain). This graduated scaffolding approach respects the child's working memory constraints while building competence.

Some pupils will show signs of phonological processing difficulties or dyslexia. These children may plateau even with high-quality instruction and scaffolding. Sounds~Write's explicit, multisensory approach is widely regarded as one of the most effective starting points for these pupils, but it is not a substitute for specialised intervention. Teachers using Sounds~Write with struggling readers should combine it with targeted phonological awareness activities, and consider specialist assessment if a child is not making progress despite intensive, well-implemented instruction.

Secondary teachers often assume that phonics instruction is only for early years and primary school. This is a significant oversight. Sounds~Write is increasingly used with secondary pupils who have not secured the code by the end of primary school. These pupils may be reading at a frustration level, guessing at words, or avoiding reading altogether. Reteaching phonics with secondary pupils requires adjustment, but it is effective.

The key difference at secondary level is pace and framing. A Year 7 pupil cannot be treated as a seven-year-old simply because they are struggling with sounds and letters. The teacher must acknowledge their cognitive development while teaching the content they have missed. Sounds~Write recommendations for secondary include: teaching the Simple Code intensively but rapidly (weeks rather than months), moving to the Complex Code quickly, and then shifting focus to morphology and etymology. Year 7 pupils can understand that the silent 'gh' in 'knight' reflects historical pronunciation, and this understanding builds literacy faster than pretending silent letters are arbitrary exceptions.

Secondary catch-up using Sounds~Write also benefits from explicit links to spelling rules pupils are failing to apply. A Year 8 pupil writing 'writting' instead of 'writing' is revealing gaps in orthographic knowledge, not carelessness. Teaching the Sounds~Write approach to doubling rules (doubling the consonant after a short vowel before adding a suffix) can transform the pupil's spelling in weeks. The approach is the same: teach the rule explicitly, model it with examples, and provide encoding practice.

Teachers implementing Sounds~Write catch-up at secondary level should expect good progress within one school year if the programme is delivered consistently (ideally 4-5 times weekly). The secondary advantage is that older pupils can understand the logic of orthography, which provides motivation for learning that younger pupils cannot access. A Year 8 pupil who understands why 'famous' is spelled with 's' (derived from 'fame') is more likely to internalise the spelling than a Year 2 pupil learning arbitrary rules.

The sound-first approach of Sounds~Write is particularly well suited to English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners. For pupils whose first language is not English, the letter names of English alphabet (a=/eɪ/, bee=/biː/) are just as foreign as the letters themselves. Teaching letters by sound rather than by name bypasses a source of confusion entirely.

EAL learners often have well-developed phonological awareness in their first language. They understand how sounds combine to form words and how words relate to one another. By beginning with sound in Sounds~Write, the teacher activates this existing knowledge rather than asking the child to start from scratch. A pupil who speaks Mandarin and is learning English can perceive that the English word 'cat' contains the phoneme /t/, even if the phoneme sequence is unfamiliar. The teacher can build on this perception by showing how /t/ is written with the letter 't'.

Sounds~Write's explicit teaching style also suits EAL learners, who may not absorb incidental information about sound-symbol relationships through immersion alone. The programme's clear modelling and repetition provides the comprehensible input that EAL learners need. Additionally, because Sounds~Write teaches both decoding and encoding together, EAL pupils develop reading and writing in parallel, reducing the risk of the common pattern where EAL learners read significantly better than they write.

Some EAL learners may benefit from preliminary phonological awareness work (teaching them to segment and blend sounds, without worrying about letters) before beginning Sounds~Write. This is particularly true for learners from languages with very different sound systems (e.g., those learning English whose first language has no equivalent to the English 'th' sounds). However, once phonological awareness is secure, Sounds~Write is highly effective for moving these learners into reading and spelling.

Teachers often ask how Sounds~Write compares to other SSP-approved schemes, particularly Jolly Phonics and Read Write Inc (RWI). Each scheme has strengths, and the comparison is instructive for understanding what Sounds~Write does distinctly.

Jolly Phonics is widely used in UK primary schools and is known for its multisensory, animated approach. Each letter is associated with an action (writing 'a' while making a snake action to represent the sound /æ/), which many young children find engaging. Jolly Phonics introduces sounds more rapidly than Sounds~Write (often 1 sound per day) and combines phonics with broader literacy instruction. However, Jolly Phonics is less explicit about the linguistic principles underlying English orthography. The "actions" are memorable but can also become a distraction if pupils focus on the movement rather than the sound itself. Jolly Phonics performs well with children who have strong visual and kinesthetic learning preferences, but it can confuse children who find the action-sound link arbitrary rather than meaningful.

Read Write Inc (RWI) is a comprehensive programme that includes phonics, vocabulary, comprehension, and writing instruction integrated together. RWI is highly structured, with consistent lesson sequences and clear progression. RWI phonics uses the term "Set 1" through "Set 3" to organise sounds, beginning with the sounds deemed most useful for building early words. RWI is particularly strong at creating coherent progression and linking phonics directly to reading connected texts. However, RWI's phonics component is less explicit about linguistic principles than Sounds~Write. RWI also tends to introduce sounds very rapidly, which can mean some children do not fully consolidate correspondences before new ones are added.

Sounds~Write differs from both in its foundation in linguistic theory. Unlike Jolly Phonics, Sounds~Write does not rely on multisensory actions; the sound itself is the focus. Unlike RWI, Sounds~Write sequences sounds based on linguistic principles (phoneme frequency, phonotactic probability) rather than practical utility. This makes Sounds~Write feel slower initially, but it produces stronger conceptual understanding of the orthographic system. Sounds~Write is also more explicitly about teaching the code itself; RWI is a full literacy programme, whereas Sounds~Write is phonics-focused and assumes schools will address comprehension, vocabulary, and writing through other means.

For schools choosing between them, the decision often comes down to teacher preference and existing infrastructure. All three are approved SSP schemes and research shows all three can produce good outcomes (EEF, 2021). Sounds~Write is the strongest choice for schools prioritising linguistic understanding and wanting a slower, deeper approach. RWI is the strongest choice for schools wanting a comprehensive, integrated literacy programme. Jolly Phonics is the strongest choice for schools wanting a highly engaging, fast-paced introduction for young children. Many schools successfully use one scheme for the majority of pupils and supplement with Sounds~Write for pupils requiring intervention or more explicit linguistic scaffolding.

Sounds~Write provides formal training and accreditation for teachers. This is not a scheme you can begin using with a manual alone; the training is essential because the teacher's role is crucial to the method's success. The training focuses on how to teach the code, not just what the code is. Teachers learn how to articulate sounds clearly, how to structure the three-part lesson sequence, how to diagnose gaps in pupil knowledge, and how to distinguish between phonological awareness gaps and orthographic gaps.

Sounds~Write offers an introductory one-day course and a more comprehensive three-day course with ongoing mentoring. After training, teachers can become accredited Sounds~Write practitioners, which signals to parents and senior leaders that the teacher has been formally prepared in the method. The company also provides detailed guidance materials, wall charts, flashcards, and online resources to support classroom implementation.

To get started with Sounds~Write, begin with the introductory training. During training, you will learn the theoretical foundation (why linguistic phonics works differently from other phonics schemes), the practical lesson structure, and how to adapt the approach for different pupil needs. You will also have the opportunity to practise teaching in micro-teaching sessions, with feedback from the trainer. This practice is valuable because teaching sounds requires precision of articulation and timing that feels unnatural until you have done it multiple times.

After training, implementation should be staged. Begin with a single phoneme or grapheme, teaching it thoroughly until pupils are secure. Gradually build from there. Do not attempt to teach the entire Simple Code in the first term; it is better to teach fewer correspondences deeply than many superficially. Many teachers find it helpful to have a colleague or mentor who has also been trained, so you can observe each other's lessons and discuss challenges that arise.

Sounds~Write is not the only phonics scheme, and no scheme is perfect for every child or every school context. However, for teachers seeking an approach grounded in linguistic research, delivering explicit and systematic instruction, and generating strong outcomes particularly for struggling readers, Sounds~Write deserves serious consideration. The investment in training pays dividends in the clarity and consistency of your phonics teaching, and in the reduced need for intervention later because most pupils will have secured the code thoroughly from the beginning.

The most important action is to base your decision on evidence and your school's context, not on fashion or ease. If your phonics programme is not producing the results you expect, particularly for lower-attaining readers, Sounds~Write training and implementation could be the intervention that shifts the dial. Begin by attending a training session, observing a Sounds~Write classroom in action if possible, and then making an informed choice about whether the approach aligns with your school's priorities and pupils' needs.

Sounds~Write is not another phonics scheme. It is a linguistically coherent system for teaching reading and spelling that starts with sound, not letter names. Created by John Walker and built on three decades of linguistic research, Sounds~Write places the sound as the primary unit of instruction, with written symbols (graphemes) following as the representation of those sounds. For teachers weary of phonics schemes that seem to work for some pupils but mysteriously fail for others, Sounds~Write offers a systematic alternative grounded in how language actually works.

The method sits comfortably within the Department for Education's approved Systematic Synthetic Phonics (SSP) programmes, but its linguistic foundations set it apart from competitors. Where many phonics schemes focus on letter-sound correspondences as isolated pairs, Sounds~Write teaches the alphabetic code as a coherent system where sounds relate to one another, and spelling choices reflect historical and linguistic patterns. This article explores how Sounds~Write works in practice, when it works best, and how to integrate it into your classroom.

Sounds~Write is a comprehensive phonics programme designed for children aged four to eleven. It teaches pupils to read and spell by starting with the sounds of English (phonemes), then teaching the written forms (graphemes) that represent those sounds. This is the reverse of how many traditional schemes work. Traditional phonics often begins with letter names (a, b, c), then tries to connect letters to sounds. Linguistic phonics begins with sounds and works toward their written representation.

The term "linguistic phonics" reflects the programme's foundation in linguistics research, particularly the work of Diane McGuinness. McGuinness (2004) argues that phonics teaching should follow the actual structure of English orthography rather than arbitrary groupings. Where letter-name-based phonics might teach "the letter 'a' makes different sounds," linguistic phonics teaches "this speech sound [æ] is represented by the letter 'a' in words like 'cat', and by other graphemes in other contexts." This shift in framing changes what children understand about reading and spelling.

The Sounds~Write approach recognises that English is not phonetically simple, but it is systematically organised. Once you understand the linguistic principles underlying English spelling, the apparent chaos resolves into patterns. The job of a Sounds~Write teacher is not to simplify these patterns away, but to teach pupils to see them clearly. A pupil who understands that the long 'e' sound can be spelled 'ee', 'ea', 'ie', 'y' (at the end of words), or 'e' (at the end of syllables) has learnt something deeper than a child who memorises "ee" and "ea" without understanding the principles that govern when each is used.

Most phonics schemes begin with letter sounds: "This is the letter 'a'. It makes the sound /æ/." The implicit message is that letters are the primary objects, and sounds are secondary. Sounds~Write inverts this. "You hear the sound /æ/ in words like 'cat', 'back', and 'map'. We write this sound with the letter 'a' in the middle of the word, but also at the beginning of 'apple'." The sound is the primary unit; the letter is one way to represent it.

This distinction matters more than it might initially appear. When a child is taught letter names first, they often slip into viewing reading as a decoding process: sound out the letters, blend them, and hope you recognise the word. This leads to the common problem of pupils who can "blend" successfully but still cannot read. They are focused on the mechanics rather than the meaning. By contrast, when a child starts with sound, the job is to recognise which sound is present and find its written form. The child remains focused on meaning from the beginning.

Consider a Year 1 pupil meeting the word 'cat' for the first time. In a letter-led approach, the teacher might say, "This is 'c', 'a', 't'. What does it say?" In Sounds~Write, the teacher says, "You can hear three sounds in 'cat': /k/, /æ/, /t/. We write /k/ with 'c' at the start. We write /æ/ with 'a' in the middle. We write /t/ with 't' at the end." The Sounds~Write version foregrounds the sounds the pupil can already perceive in their own speech, making the link to writing clearer and less abstract.

This sound-first approach also explains Sounds~Write's strength with struggling readers. If a pupil has not yet automated the arbitrary association between a letter name and a letter sound, they are already working with a double abstraction. They must remember what the letter name is, then what sound it makes. If the teacher bypasses the letter name entirely and works with sound, the cognitive load drops immediately. This is why the programme performs well with children who have phonological awareness difficulties, SEND pupils, and EAL learners for whom letter names in English are unfamiliar.

The Sounds~Write curriculum organises English orthography into three tiers: the Simple Code, the Complex Code, and the Extended Code. This structure makes the system feel manageable rather than overwhelming.

The Simple Code covers single graphemes representing single phonemes. Pupils learn that /m/ is written 'm', /d/ is written 'd', /æ/ is written 'a', and so on. There are approximately 44 phonemes in English, but far fewer graphemes needed to represent them initially. A Year 1 class working through the Simple Code learns to read and spell simple words like 'mat', 'sit', 'dog', 'red' by combining these single letter-sound correspondences. The teaching is explicit: "Here are the sounds we can make, and here are the letters we use to write them."

The Complex Code begins when pupils have consolidated the Simple Code. It addresses situations where a single phoneme is represented by more than one grapheme, or where a single grapheme represents more than one phoneme. For example, /k/ can be written 'c' or 'k' depending on the following vowel. The phoneme /ʃ/ (as in 'sheep') is written 'sh'. The grapheme 'ough' represents different phonemes in 'tough', 'through', and 'cough'. These are not exceptions; they are predictable patterns based on English phonotactics and historical spelling conventions. Teaching them systematically rather than treating them as sight words strengthens reading resilience.

The Extended Code covers the less frequent patterns and the historical layers of English orthography. This includes silent letters, borrowed letter combinations from French and Latin, and morphological relationships (where spelling patterns reflect word meaning and relatedness rather than pure sound). For instance, understanding that 'castle' has a silent 't' becomes logical once pupils learn that 'castle' is related to 'castle' (no silent 't' in the Italian source word), but English orthography preserves the 't' from historical pronunciation. A teacher explaining this is not asking pupils to memorise arbitrary rules; the teacher is showing pupils that spelling reflects deeper language structure.

In classroom practice, this three-tier structure gives you a clear roadmap. In Year 1, you focus on the Simple Code, ensuring every pupil has rock-solid knowledge of basic letter-sound correspondences and can blend and segment three-letter consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words. In Year 2, you layer the Complex Code, teaching digraphs, trigraphs, and split vowel digraphs. By Year 3 and beyond, you are addressing the Extended Code and morphology. This prevents the chaos of teaching 'sight words', which is how many programmes handle everything beyond the basic correspondences.

Every Sounds~Write lesson follows a consistent structure: teaching (modelling), guided practice, and independent application. This routine builds automaticity and reduces cognitive load, which is particularly important for early readers who are still developing their working memory capacity (Sweller, 1988).

The teaching phase involves explicit modelling by the teacher. If teaching the grapheme 'ai' (one of the Complex Code correspondences for the long 'a' sound), the teacher might display a card with 'ai' on it and say aloud: "I can see the grapheme 'a' and 'i'. Together they write the sound /eɪ/ as in 'rain', 'train', 'paint'." The teacher then articulates the sound clearly, links it to familiar words, and asks pupils to repeat. There is no discovery learning here; the rule is stated directly. This clarity is deliberate. The teacher is providing a direct instruction model that transfers knowledge efficiently.

The guided practice phase involves the teacher and pupils working together. The teacher might display a word like 'braid' and ask the class to identify each grapheme and say each sound aloud before blending. The teacher provides feedback immediately: if a pupil says the wrong sound, the teacher corrects it without lengthy explanation. "No, 'ai' here says /eɪ/. Let's say it together." This correction is brief and focused because the rule has already been taught. Pupils are not figuring out rules; they are applying known rules to new words.

The independent application phase involves pupils working alone or in pairs with words or sentences containing the target grapheme. This might involve matching words to pictures, completing partially written words, or writing words from dictation. The teacher circulates, observing which pupils can apply the rule and which need reteaching. This formative assessment (Dylan Wiliam's work on formative assessment emphasizes this loop) informs whether the class moves on or revisits the correspondence.

A typical Year 1 lesson might last 15-20 minutes. A teacher introducing the grapheme 'e' (saying /ɛ/) might spend 3 minutes teaching it, 5 minutes on guided practice with words like 'pen', 'leg', 'men', and 10 minutes on independent tasks. The consistency of this structure is intentional. Pupils begin to anticipate the flow, reducing anxiety and freeing cognitive resources for learning the content itself.

Sounds~Write teaches reading (decoding) and spelling (encoding) simultaneously, using the same sound knowledge. This is not unique to Sounds~Write, but the programme's explicit commitment to dual teaching is notable. When a child learns the correspondence /æ/ = 'a', they are simultaneously learning to read words with 'a' and to spell words containing /æ/. There is no delay; encoding happens from day one.

This matters because reading and spelling are not identical processes. A child might be able to read a word (recognize it from its visual form) without being able to spell it (retrieve and sequence the correct letters). Traditional instruction often treats spelling as secondary, something to tackle once reading is secure. Sounds~Write rejects this hierarchy. Spelling reveals which phonemes a child can perceive and which grapheme choices they understand. If a child writes 'kat' instead of 'cat', the teacher knows something important about the child's phonological awareness and grapheme knowledge.

In practice, every Sounds~Write lesson includes an encoding component. After pupils have practised decoding words with 'a', the teacher might ask them to write simple words from dictation: 'cat', 'sat', 'mat'. The teacher says the word slowly, pupils identify the sounds, and they write the corresponding graphemes. This encoding task serves multiple purposes. It provides retrieval practice, which strengthens memory for the correspondence. It gives the teacher diagnostic information about which pupils have confused the link between sound and symbol. It also prevents a common failure pattern: a child who can read words but cannot spell them may eventually stop reading, because they suspect they don't truly understand the code.

The linguistic principle underlying this is that orthography (spelling) directly represents phonology (sound). Therefore, to become secure in the phonological system, a child must be able to move fluidly between hearing sounds and writing symbols, and between seeing symbols and hearing sounds. Sounds~Write treats spelling not as a separate subject, but as the other half of literacy instruction.

The sequence in which Sounds~Write introduces graphemes is not arbitrary. It follows principles of phoneme frequency, phonotactic probability, and morphological productivity. This differs from schemes that might introduce letters in alphabetical order or based on the letters children already know from their names.

Sounds~Write prioritises phonemes that appear frequently in English speech, particularly in the consonants and short vowels that form the structure of most early-years words. The phoneme /m/ appears in many early words (mum, mad, mat), so 'm' is taught early. The phoneme /ŋ/ (as in 'sing') is less frequent, so it may come later. For vowels, the short vowels (/æ/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /ɒ/, /ʌ/) are taught before long vowels because CVC words with short vowels (cat, sit, dog) are more numerous in early readers.

The sequence also respects phonotactic principles. In English, some consonant clusters are common and easy to blend (bl, st, tr), while others are rare or difficult (thr before a vowel requires careful articulatory control). Sounds~Write introduces frequent clusters early and later clusters only once pupils are confident. This prevents the frustration of trying to read words with unfamiliar sound combinations before pupils have the phonological stability to manage them.

A typical Year 1 sequence in Sounds~Write might look like this: introduce 10-15 consonants (including easy clusters like 'st' and 'pl') and the five short vowels over the first two terms. Then introduce digraphs (ch, sh, th) and common long vowel correspondences (ai, ee, oa) in term three and early Year 2. This pace seems slower than many schemes, which introduce 2-3 graphemes per week. However, the Sounds~Write pace is deceptive. Each grapheme is taught thoroughly, with multiple encoding and decoding opportunities before new graphemes are added. The result is fewer pupils needing intervention or reteaching later.

Despite the systematic approach, some pupils will plateau. They may master the Simple Code but struggle when Complex Code patterns are introduced. Others may be fluent readers but poor spellers, or vice versa. Sounds~Write has embedded differentiation strategies to address these situations.

The first response to a plateau is diagnostic. Sounds~Write emphasises identifying precisely which correspondence a child has not yet secured. A child who reads 'cat' and 'mat' but cannot read 'sat' has not yet fully internalised the /s/ = 's' correspondence. The teacher's job is not to reteach the whole alphabet; it is to focus intensive practice on 's'. This targeted approach, informed by formative assessment, is far more efficient than whole-group reteaching.

If a pupil plateaus on a specific correspondence, Sounds~Write recommends breaking the learning into smaller chunks. If a child struggles with the grapheme 'ai' representing /eɪ/, the teacher might begin by teaching 'ai' in only initial-position words (aim, air, aid), where the child can focus on the new grapheme combination. Only once the child is confident with these words would the teacher introduce 'ai' in final position (wait, brain) or in complex consonant clusters (train, drain). This graduated scaffolding approach respects the child's working memory constraints while building competence.

Some pupils will show signs of phonological processing difficulties or dyslexia. These children may plateau even with high-quality instruction and scaffolding. Sounds~Write's explicit, multisensory approach is widely regarded as one of the most effective starting points for these pupils, but it is not a substitute for specialised intervention. Teachers using Sounds~Write with struggling readers should combine it with targeted phonological awareness activities, and consider specialist assessment if a child is not making progress despite intensive, well-implemented instruction.

Secondary teachers often assume that phonics instruction is only for early years and primary school. This is a significant oversight. Sounds~Write is increasingly used with secondary pupils who have not secured the code by the end of primary school. These pupils may be reading at a frustration level, guessing at words, or avoiding reading altogether. Reteaching phonics with secondary pupils requires adjustment, but it is effective.

The key difference at secondary level is pace and framing. A Year 7 pupil cannot be treated as a seven-year-old simply because they are struggling with sounds and letters. The teacher must acknowledge their cognitive development while teaching the content they have missed. Sounds~Write recommendations for secondary include: teaching the Simple Code intensively but rapidly (weeks rather than months), moving to the Complex Code quickly, and then shifting focus to morphology and etymology. Year 7 pupils can understand that the silent 'gh' in 'knight' reflects historical pronunciation, and this understanding builds literacy faster than pretending silent letters are arbitrary exceptions.

Secondary catch-up using Sounds~Write also benefits from explicit links to spelling rules pupils are failing to apply. A Year 8 pupil writing 'writting' instead of 'writing' is revealing gaps in orthographic knowledge, not carelessness. Teaching the Sounds~Write approach to doubling rules (doubling the consonant after a short vowel before adding a suffix) can transform the pupil's spelling in weeks. The approach is the same: teach the rule explicitly, model it with examples, and provide encoding practice.

Teachers implementing Sounds~Write catch-up at secondary level should expect good progress within one school year if the programme is delivered consistently (ideally 4-5 times weekly). The secondary advantage is that older pupils can understand the logic of orthography, which provides motivation for learning that younger pupils cannot access. A Year 8 pupil who understands why 'famous' is spelled with 's' (derived from 'fame') is more likely to internalise the spelling than a Year 2 pupil learning arbitrary rules.

The sound-first approach of Sounds~Write is particularly well suited to English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners. For pupils whose first language is not English, the letter names of English alphabet (a=/eɪ/, bee=/biː/) are just as foreign as the letters themselves. Teaching letters by sound rather than by name bypasses a source of confusion entirely.

EAL learners often have well-developed phonological awareness in their first language. They understand how sounds combine to form words and how words relate to one another. By beginning with sound in Sounds~Write, the teacher activates this existing knowledge rather than asking the child to start from scratch. A pupil who speaks Mandarin and is learning English can perceive that the English word 'cat' contains the phoneme /t/, even if the phoneme sequence is unfamiliar. The teacher can build on this perception by showing how /t/ is written with the letter 't'.

Sounds~Write's explicit teaching style also suits EAL learners, who may not absorb incidental information about sound-symbol relationships through immersion alone. The programme's clear modelling and repetition provides the comprehensible input that EAL learners need. Additionally, because Sounds~Write teaches both decoding and encoding together, EAL pupils develop reading and writing in parallel, reducing the risk of the common pattern where EAL learners read significantly better than they write.

Some EAL learners may benefit from preliminary phonological awareness work (teaching them to segment and blend sounds, without worrying about letters) before beginning Sounds~Write. This is particularly true for learners from languages with very different sound systems (e.g., those learning English whose first language has no equivalent to the English 'th' sounds). However, once phonological awareness is secure, Sounds~Write is highly effective for moving these learners into reading and spelling.

Teachers often ask how Sounds~Write compares to other SSP-approved schemes, particularly Jolly Phonics and Read Write Inc (RWI). Each scheme has strengths, and the comparison is instructive for understanding what Sounds~Write does distinctly.

Jolly Phonics is widely used in UK primary schools and is known for its multisensory, animated approach. Each letter is associated with an action (writing 'a' while making a snake action to represent the sound /æ/), which many young children find engaging. Jolly Phonics introduces sounds more rapidly than Sounds~Write (often 1 sound per day) and combines phonics with broader literacy instruction. However, Jolly Phonics is less explicit about the linguistic principles underlying English orthography. The "actions" are memorable but can also become a distraction if pupils focus on the movement rather than the sound itself. Jolly Phonics performs well with children who have strong visual and kinesthetic learning preferences, but it can confuse children who find the action-sound link arbitrary rather than meaningful.

Read Write Inc (RWI) is a comprehensive programme that includes phonics, vocabulary, comprehension, and writing instruction integrated together. RWI is highly structured, with consistent lesson sequences and clear progression. RWI phonics uses the term "Set 1" through "Set 3" to organise sounds, beginning with the sounds deemed most useful for building early words. RWI is particularly strong at creating coherent progression and linking phonics directly to reading connected texts. However, RWI's phonics component is less explicit about linguistic principles than Sounds~Write. RWI also tends to introduce sounds very rapidly, which can mean some children do not fully consolidate correspondences before new ones are added.

Sounds~Write differs from both in its foundation in linguistic theory. Unlike Jolly Phonics, Sounds~Write does not rely on multisensory actions; the sound itself is the focus. Unlike RWI, Sounds~Write sequences sounds based on linguistic principles (phoneme frequency, phonotactic probability) rather than practical utility. This makes Sounds~Write feel slower initially, but it produces stronger conceptual understanding of the orthographic system. Sounds~Write is also more explicitly about teaching the code itself; RWI is a full literacy programme, whereas Sounds~Write is phonics-focused and assumes schools will address comprehension, vocabulary, and writing through other means.

For schools choosing between them, the decision often comes down to teacher preference and existing infrastructure. All three are approved SSP schemes and research shows all three can produce good outcomes (EEF, 2021). Sounds~Write is the strongest choice for schools prioritising linguistic understanding and wanting a slower, deeper approach. RWI is the strongest choice for schools wanting a comprehensive, integrated literacy programme. Jolly Phonics is the strongest choice for schools wanting a highly engaging, fast-paced introduction for young children. Many schools successfully use one scheme for the majority of pupils and supplement with Sounds~Write for pupils requiring intervention or more explicit linguistic scaffolding.

Sounds~Write provides formal training and accreditation for teachers. This is not a scheme you can begin using with a manual alone; the training is essential because the teacher's role is crucial to the method's success. The training focuses on how to teach the code, not just what the code is. Teachers learn how to articulate sounds clearly, how to structure the three-part lesson sequence, how to diagnose gaps in pupil knowledge, and how to distinguish between phonological awareness gaps and orthographic gaps.

Sounds~Write offers an introductory one-day course and a more comprehensive three-day course with ongoing mentoring. After training, teachers can become accredited Sounds~Write practitioners, which signals to parents and senior leaders that the teacher has been formally prepared in the method. The company also provides detailed guidance materials, wall charts, flashcards, and online resources to support classroom implementation.

To get started with Sounds~Write, begin with the introductory training. During training, you will learn the theoretical foundation (why linguistic phonics works differently from other phonics schemes), the practical lesson structure, and how to adapt the approach for different pupil needs. You will also have the opportunity to practise teaching in micro-teaching sessions, with feedback from the trainer. This practice is valuable because teaching sounds requires precision of articulation and timing that feels unnatural until you have done it multiple times.

After training, implementation should be staged. Begin with a single phoneme or grapheme, teaching it thoroughly until pupils are secure. Gradually build from there. Do not attempt to teach the entire Simple Code in the first term; it is better to teach fewer correspondences deeply than many superficially. Many teachers find it helpful to have a colleague or mentor who has also been trained, so you can observe each other's lessons and discuss challenges that arise.

Sounds~Write is not the only phonics scheme, and no scheme is perfect for every child or every school context. However, for teachers seeking an approach grounded in linguistic research, delivering explicit and systematic instruction, and generating strong outcomes particularly for struggling readers, Sounds~Write deserves serious consideration. The investment in training pays dividends in the clarity and consistency of your phonics teaching, and in the reduced need for intervention later because most pupils will have secured the code thoroughly from the beginning.

The most important action is to base your decision on evidence and your school's context, not on fashion or ease. If your phonics programme is not producing the results you expect, particularly for lower-attaining readers, Sounds~Write training and implementation could be the intervention that shifts the dial. Begin by attending a training session, observing a Sounds~Write classroom in action if possible, and then making an informed choice about whether the approach aligns with your school's priorities and pupils' needs.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Organization","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/#org","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/5b69a01ba2e40996a5e055f4_structural-learning-logo.png"}},{"@type":"Person","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paul-main/#person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paul-main","jobTitle":"Founder","affiliation":{"@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/#org"}},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/soundswrite-teachers-guide-linguistic-phonics#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Sounds~Write: A Teacher's Guide to Linguistic Phonics","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/soundswrite-teachers-guide-linguistic-phonics"}]},{"@type":"BlogPosting","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/soundswrite-teachers-guide-linguistic-phonics#article","headline":"Sounds~Write: A Teacher's Guide to Linguistic Phonics","description":"","author":{"@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paul-main/#person"},"publisher":{"@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/#org"},"datePublished":"2026-02-19","dateModified":"2026-02-19","inLanguage":"en-GB"}]}