Evidence-Informed Practice: Developing Research-Literate Teachers

Learn how to develop evidence-informed practitioners in schools. Engage with research, evaluate evidence, and translate findings into classroom practice.

Learn how to develop evidence-informed practitioners in schools. Engage with research, evaluate evidence, and translate findings into classroom practice.

Evidence-informed practice (EIP) is an approach to teaching that integrates the best available resea rch evidence with professional expertise and knowledge of the specific students, their cultural capital, and context. Unlike evidence-based practice, which implies direct application of research findings, evidence-informed practice acknowledges that teaching involves complex systems and that research must be interpreted and adapted for individual classrooms.

The term deliberately uses 'informed' rather than 'based' to recognise that teachers are not simply implementing research prescriptions. Instead, they are professional decision-makers who use evidence as one input among several, including their own expertise, knowledge of their students, and understanding of their school context.

Teachers need evidence-informed practice to avoid educational fads and make decisions based on proven strategies rather than intuition or tradition. This approach combines research findings with professional expertise and student knowledge to improve learning outcomes. It protects valuable classroom time from being wasted on methods that lack empirical support, like learning styles or Brain Gym.

Education has historically been vulnerable to fads, trends, and approaches lacking empirical support. Learning styles, Brain Gym, and discovery learning without scaffolding strategies have all enjoyed popularity despite limited or contradictory evidence. Eviden ce-informed practice provides a framework for evaluating such claims critically.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has documented significant variation in teaching effectiveness, with the difference between effective and ineffective approaches potentially representing months of additional learning progress. Teachers who engage with evidence systematically are better equipped to identify high-impact strategies and avoid wasting time on approaches unlikely to benefit their students.

Research from the Chartered College of Teaching indicates that teachers who engage regularly with educational research report greater confidence in their professional judgement and higher job satisfaction. Evidence engagement is not about undermining teacher autonomy but about enhancing it through better information.

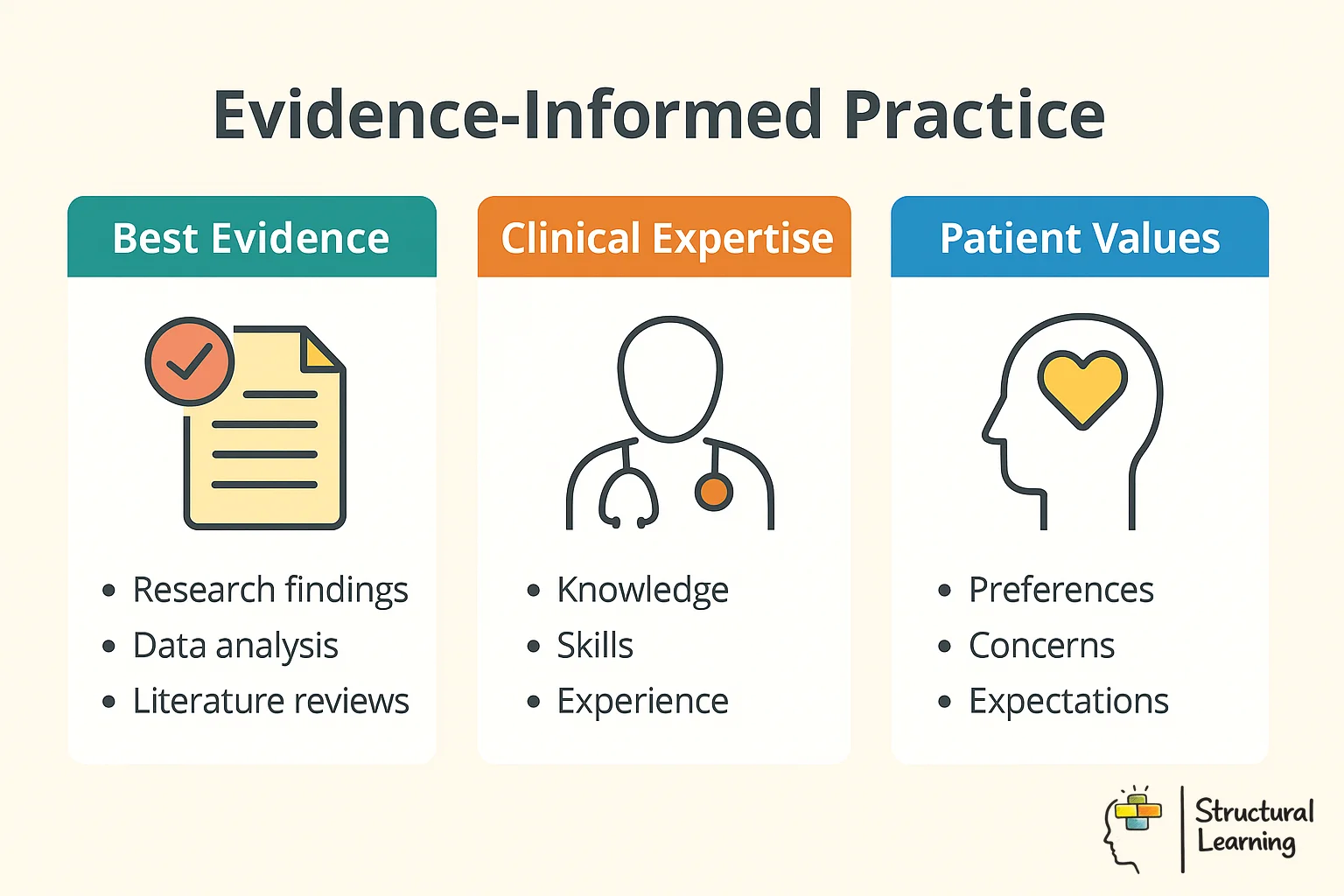

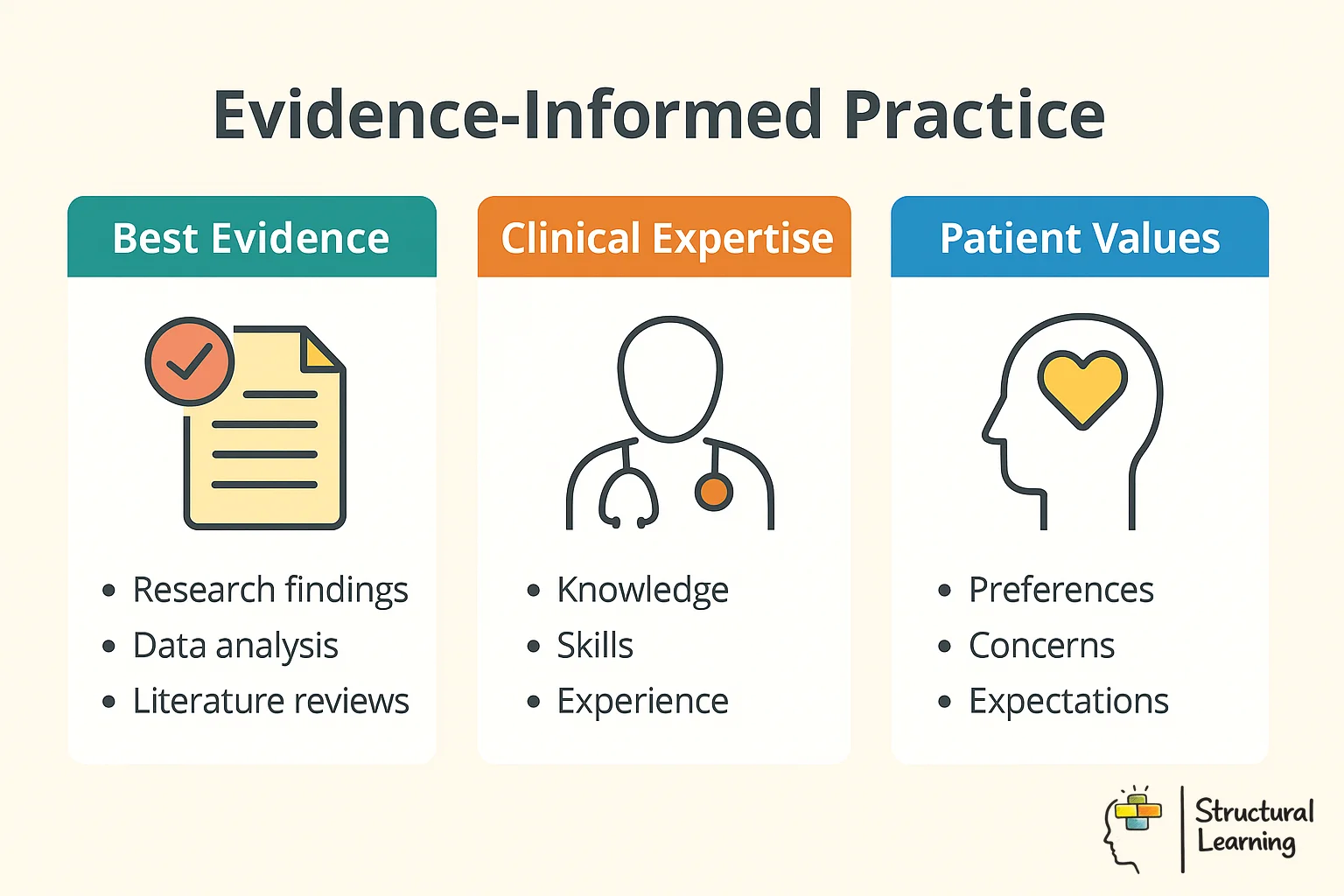

The three sources of evidence in teaching are research evidence from academic studies, professional expertise gained through classroom experience, and specific knowledge about your students and their context. These sources work together to inform teaching decisions, with no single source being sufficient on its own. Teachers synthesize all three to create approaches that are both research-backed and contextually appropriate.

Evidence-informed practice draws on three interconnected sources, each essential for effective decision-making:

This includes findings from educational research, cognitive science, and related fields. High-quality sources include systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and well-designed randomised controlled trials. The EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit provides accessible summaries of research on common educational interventions.

Teachers accumulate practical wisdom through experience, including knowledge of what works in their specific context, how to adapt strategies for different learners, and how to manage the complex dynamics of classroom life. This expertise is essential for interpreting and applying research findings appropriately, particularly when working with students with special educational needs.

This includes knowledge of your specific students, school culture, available resources, and community context. It also encompasses local data such as assessment results, attendance patterns, and feedback from students and parents. What works in one context may not transfer directly to another.

Teachers can evaluate research quality by checking for peer review, examining sample sizes and methodology, and looking for replication studies. Key indicators include whether findings have been tested in real classroom settings and if results are consistent across different contexts. Understanding basic research concepts like effect sizes and control groups helps distinguish robust findings from questionable claims.

Not all research is created equal. Evidence-informed practitioners develop the skills to evaluate research quality and relevance, including developing their critical thinking abilities. Key questions to ask include:

What was the sample size and context? Small studies or those conducted in very different contexts may not generalise to your situation. A study of university students in laboratory conditions may not apply to primary school children in busy classrooms.

Was there a comparison group? Without a control or comparison group, it is difficult to know whether observed improvements resulted from the intervention or other factors.

Who conducted and funded the research? Research conducted or funded by organisations selling related products or services may be subject to bias, even unintentionally.

Has it been replicated? Single studies, however well-designed, can produce misleading results. Findings that have been replicated across multiple studies and contexts are more reliable, particularly when considering strategies that impact student engagement.

What is the effect size? Statistical significance does not always mean practical significance. An intervention might produce a measurable effect that is statistically significant but so small as to be irrelevant in a real-world setting. Understanding effect sizes, such as Cohen's d, allows you to gauge the practical importance of research findings. A larger effect size suggests a more substantial impact.

Was the research peer-reviewed? Peer review is a process where experts in the field scrutinise research before publication, increasing its reliability. Look for research published in reputable academic journals with a rigorous peer-review process.

Examples of evidence-informed practice include using spaced repetition based on cognitive science to improve memory, implementing reciprocal teaching based on research in reading comprehension, and adopting behaviour management techniques with proven effects on student behaviour. Teachers integrate research insights with their own experience and understanding of students to improve these methods for their specific classrooms.

Spaced Repetition: Research shows that spacing out learning over time improves long-term retention. Teachers can apply this by revisiting key concepts at increasing intervals rather than cramming information into one lesson.

Reciprocal Teaching: This strategy, based on research in reading comprehension, involves students taking turns leading discussions and summarising, questioning, clarifying, and predicting. Teachers can model these behaviours and provide scaffolding to support students as they learn.

Explicit Instruction: Research consistently demonstrates the effectiveness of explicit instruction, especially for students who struggle. Teachers provide clear, direct instruction, model skills, and provide guided practice before independent work. This approach is particularly helpful for teaching complex concepts or skills, such as mathematical procedures.

Formative Assessment: Research highlights the power of formative assessment to improve student learning. Teachers use regular, low-stakes assessments to monitor student progress and adjust their teaching accordingly, providing timely feedback to students.

Schools can support evidence-informed practice by allocating time for professional development, creating research learning communities, providing access to research databases, and developing a culture of inquiry. Leadership plays a crucial role in promoting and valuing evidence-informed decision-making throughout the school.

Allocating Time for Professional Development: Teachers need time to engage with research, reflect on their practice, and collaborate with colleagues. Schools can dedicate professional development days to evidence-informed practice and provide ongoing support for teachers.

Creating Research Learning Communities: These communities provide a forum for teachers to discuss research, share ideas, and support each other in implementing evidence-informed strategies. Schools can facilitate these communities by providing meeting space, resources, and facilitation support.

Providing Access to Research Databases: Schools can provide teachers with access to research databases and online resources, such as the EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit and the Chartered College of Teaching's Research Database. This gives teachers access to the latest research findings and evidence-based strategies.

Developing a Culture of Inquiry: Schools can creates a culture of inquiry by encouraging teachers to ask questions, experiment with new approaches, and share their findings with colleagues. This creates a learning environment where evidence is valued and used to improve teaching and learning.

Evidence-informed practice (EIP) is an approach to teaching that integrates the best available resea rch evidence with professional expertise and knowledge of the specific students, their cultural capital, and context. Unlike evidence-based practice, which implies direct application of research findings, evidence-informed practice acknowledges that teaching involves complex systems and that research must be interpreted and adapted for individual classrooms.

The term deliberately uses 'informed' rather than 'based' to recognise that teachers are not simply implementing research prescriptions. Instead, they are professional decision-makers who use evidence as one input among several, including their own expertise, knowledge of their students, and understanding of their school context.

Teachers need evidence-informed practice to avoid educational fads and make decisions based on proven strategies rather than intuition or tradition. This approach combines research findings with professional expertise and student knowledge to improve learning outcomes. It protects valuable classroom time from being wasted on methods that lack empirical support, like learning styles or Brain Gym.

Education has historically been vulnerable to fads, trends, and approaches lacking empirical support. Learning styles, Brain Gym, and discovery learning without scaffolding strategies have all enjoyed popularity despite limited or contradictory evidence. Eviden ce-informed practice provides a framework for evaluating such claims critically.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has documented significant variation in teaching effectiveness, with the difference between effective and ineffective approaches potentially representing months of additional learning progress. Teachers who engage with evidence systematically are better equipped to identify high-impact strategies and avoid wasting time on approaches unlikely to benefit their students.

Research from the Chartered College of Teaching indicates that teachers who engage regularly with educational research report greater confidence in their professional judgement and higher job satisfaction. Evidence engagement is not about undermining teacher autonomy but about enhancing it through better information.

The three sources of evidence in teaching are research evidence from academic studies, professional expertise gained through classroom experience, and specific knowledge about your students and their context. These sources work together to inform teaching decisions, with no single source being sufficient on its own. Teachers synthesize all three to create approaches that are both research-backed and contextually appropriate.

Evidence-informed practice draws on three interconnected sources, each essential for effective decision-making:

This includes findings from educational research, cognitive science, and related fields. High-quality sources include systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and well-designed randomised controlled trials. The EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit provides accessible summaries of research on common educational interventions.

Teachers accumulate practical wisdom through experience, including knowledge of what works in their specific context, how to adapt strategies for different learners, and how to manage the complex dynamics of classroom life. This expertise is essential for interpreting and applying research findings appropriately, particularly when working with students with special educational needs.

This includes knowledge of your specific students, school culture, available resources, and community context. It also encompasses local data such as assessment results, attendance patterns, and feedback from students and parents. What works in one context may not transfer directly to another.

Teachers can evaluate research quality by checking for peer review, examining sample sizes and methodology, and looking for replication studies. Key indicators include whether findings have been tested in real classroom settings and if results are consistent across different contexts. Understanding basic research concepts like effect sizes and control groups helps distinguish robust findings from questionable claims.

Not all research is created equal. Evidence-informed practitioners develop the skills to evaluate research quality and relevance, including developing their critical thinking abilities. Key questions to ask include:

What was the sample size and context? Small studies or those conducted in very different contexts may not generalise to your situation. A study of university students in laboratory conditions may not apply to primary school children in busy classrooms.

Was there a comparison group? Without a control or comparison group, it is difficult to know whether observed improvements resulted from the intervention or other factors.

Who conducted and funded the research? Research conducted or funded by organisations selling related products or services may be subject to bias, even unintentionally.

Has it been replicated? Single studies, however well-designed, can produce misleading results. Findings that have been replicated across multiple studies and contexts are more reliable, particularly when considering strategies that impact student engagement.

What is the effect size? Statistical significance does not always mean practical significance. An intervention might produce a measurable effect that is statistically significant but so small as to be irrelevant in a real-world setting. Understanding effect sizes, such as Cohen's d, allows you to gauge the practical importance of research findings. A larger effect size suggests a more substantial impact.

Was the research peer-reviewed? Peer review is a process where experts in the field scrutinise research before publication, increasing its reliability. Look for research published in reputable academic journals with a rigorous peer-review process.

Examples of evidence-informed practice include using spaced repetition based on cognitive science to improve memory, implementing reciprocal teaching based on research in reading comprehension, and adopting behaviour management techniques with proven effects on student behaviour. Teachers integrate research insights with their own experience and understanding of students to improve these methods for their specific classrooms.

Spaced Repetition: Research shows that spacing out learning over time improves long-term retention. Teachers can apply this by revisiting key concepts at increasing intervals rather than cramming information into one lesson.

Reciprocal Teaching: This strategy, based on research in reading comprehension, involves students taking turns leading discussions and summarising, questioning, clarifying, and predicting. Teachers can model these behaviours and provide scaffolding to support students as they learn.

Explicit Instruction: Research consistently demonstrates the effectiveness of explicit instruction, especially for students who struggle. Teachers provide clear, direct instruction, model skills, and provide guided practice before independent work. This approach is particularly helpful for teaching complex concepts or skills, such as mathematical procedures.

Formative Assessment: Research highlights the power of formative assessment to improve student learning. Teachers use regular, low-stakes assessments to monitor student progress and adjust their teaching accordingly, providing timely feedback to students.

Schools can support evidence-informed practice by allocating time for professional development, creating research learning communities, providing access to research databases, and developing a culture of inquiry. Leadership plays a crucial role in promoting and valuing evidence-informed decision-making throughout the school.

Allocating Time for Professional Development: Teachers need time to engage with research, reflect on their practice, and collaborate with colleagues. Schools can dedicate professional development days to evidence-informed practice and provide ongoing support for teachers.

Creating Research Learning Communities: These communities provide a forum for teachers to discuss research, share ideas, and support each other in implementing evidence-informed strategies. Schools can facilitate these communities by providing meeting space, resources, and facilitation support.

Providing Access to Research Databases: Schools can provide teachers with access to research databases and online resources, such as the EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit and the Chartered College of Teaching's Research Database. This gives teachers access to the latest research findings and evidence-based strategies.

Developing a Culture of Inquiry: Schools can creates a culture of inquiry by encouraging teachers to ask questions, experiment with new approaches, and share their findings with colleagues. This creates a learning environment where evidence is valued and used to improve teaching and learning.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/developing-evidence-informed-practitioners#article","headline":"Evidence-Informed Practice: Developing Research-Literate Teachers","description":"Learn how to develop evidence-informed practitioners in schools. Understand how to engage with research, evaluate evidence, and translate findings into...","datePublished":"2022-05-16T15:16:26.562Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/developing-evidence-informed-practitioners"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a140ee4701aee904a6185_696a140d7de493f6a7b7cc6a_developing-evidence-informed-practitioners-infographic.webp","wordCount":2023},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/developing-evidence-informed-practitioners#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Evidence-Informed Practice: Developing Research-Literate Teachers","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/developing-evidence-informed-practitioners"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What Is Evidence-Informed Practice?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Evidence-informed practice (EIP) is an approach to teaching that integrates the best available resea rch evidence with professional expertise and knowledge of the specific students, their cultural capital, and context. Unlike evidence-based practice, which implies direct application of research findings, evidence-informed practice acknowledges that teaching involves complex systems and that research must be interpreted and adapted for individual classrooms."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why Do Teachers Need Evidence-Informed Practice?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers need evidence-informed practice to avoid educational fads and make decisions based on proven strategies rather than intuition or tradition. This approach combines research findings with professional expertise and student knowledge to improve learning outcomes. It protects valuable classroom time from being wasted on methods that lack empirical support, like learning styles or Brain Gym."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Are the Three Sources of Evidence in Teaching?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"The three sources of evidence in teaching are research evidence from academic studies, professional expertise gained through classroom experience, and specific knowledge about your students and their context. These sources work together to inform teaching decisions, with no single source being sufficient on its own. Teachers synthesize all three to create approaches that are both research-backed and contextually appropriate."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Teachers Evaluate Educational Research Quality?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Teachers can evaluate research quality by checking for peer review, examining sample sizes and methodology, and looking for replication studies. Key indicators include whether findings have been tested in real classroom settings and if results are consistent across different contexts. Understanding basic research concepts like effect sizes and control groups helps distinguish robust findings from questionable claims."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What Are Some Examples of Evidence-Informed Practice in Action?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Examples of evidence-informed practice include using spaced repetition based on cognitive science to improve memory, implementing reciprocal teaching based on research in reading comprehension, and adopting behaviour management techniques with proven effects on student behaviour. Teachers integrate research insights with their own experience and understanding of students to improve these methods for their specific classrooms."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Can Schools Support Evidence-Informed Practice?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Schools can support evidence-informed practice by allocating time for professional development, creating research learning communities, providing access to research databases, and developing a culture of inquiry. Leadership plays a crucial role in promoting and valuing evidence-informed decision-making throughout the school."}}]}]}