Updated on

February 19, 2026

Curiosity-Driven Learning: What Every Teacher Needs to Know

|

February 19, 2026

Updated on

February 19, 2026

|

February 19, 2026

Curiosity is not optional in education. It is the engine that drives voluntary effort, enables memory formation, and sustains learning when tasks become difficult. Yet classroom conditions often suppress curiosity rather than nurture it, and teachers frequently confuse curiosity with interest or novelty. This article examines the cognitive science of curiosity, provides practical strategies to trigger it systematically, and offers tools to observe whether your students are genuinely curious or merely compliant.

Curiosity is not one thing. Daniel Berlyne's foundational distinction between epistemic and perceptual curiosity (1960) remains the most useful framework for teachers. Epistemic curiosity is the desire to know; it arises when you encounter a gap between what you know and what you want to know. Perceptual curiosity, by contrast, is the desire to perceive something novel or complex; it attracts attention but does not necessarily drive learning.

In your classroom, these operate differently. When a Year 5 student is puzzled by why salt dissolves in water but sand does not, they are in a state of epistemic curiosity. They want to understand. When the same student is momentarily distracted by a colourful poster on the wall, that is perceptual curiosity. It grabs attention but fades quickly. Diversive curiosity is a third form: the desire for novel experience rather than the resolution of a specific knowledge gap. It is what drives students to open a book about medieval castles when they have no learning target related to castles. In classrooms that prioritise motivation above all else, diversive curiosity is often mistaken for engagement (Berlyne, 1960).

Epistemic curiosity is what you should cultivate. It is relatively stable, leads to deeper processing, and improves retention. Here is a practical distinction: if your student wants to know the answer to a question, they are epistemically curious. If they are simply attracted to something shiny or unexpected, they are experiencing perceptual curiosity, which is fleeting.

Classroom example: In a secondary English class, the teacher shows two opening lines: "The sky was blue." and "The sky dripped rust." Without explanation, students ask which is "better" and why the second one breaks the rule. That is epistemic curiosity. They want to understand. If the teacher had simply shown a dramatic image of a rust-coloured sunset and asked students to write about it, students might produce creative work, but they would not necessarily be curious about how and why writers make deliberate choices. The difference is whether students are trying to resolve a gap in understanding, not whether they are engaged.

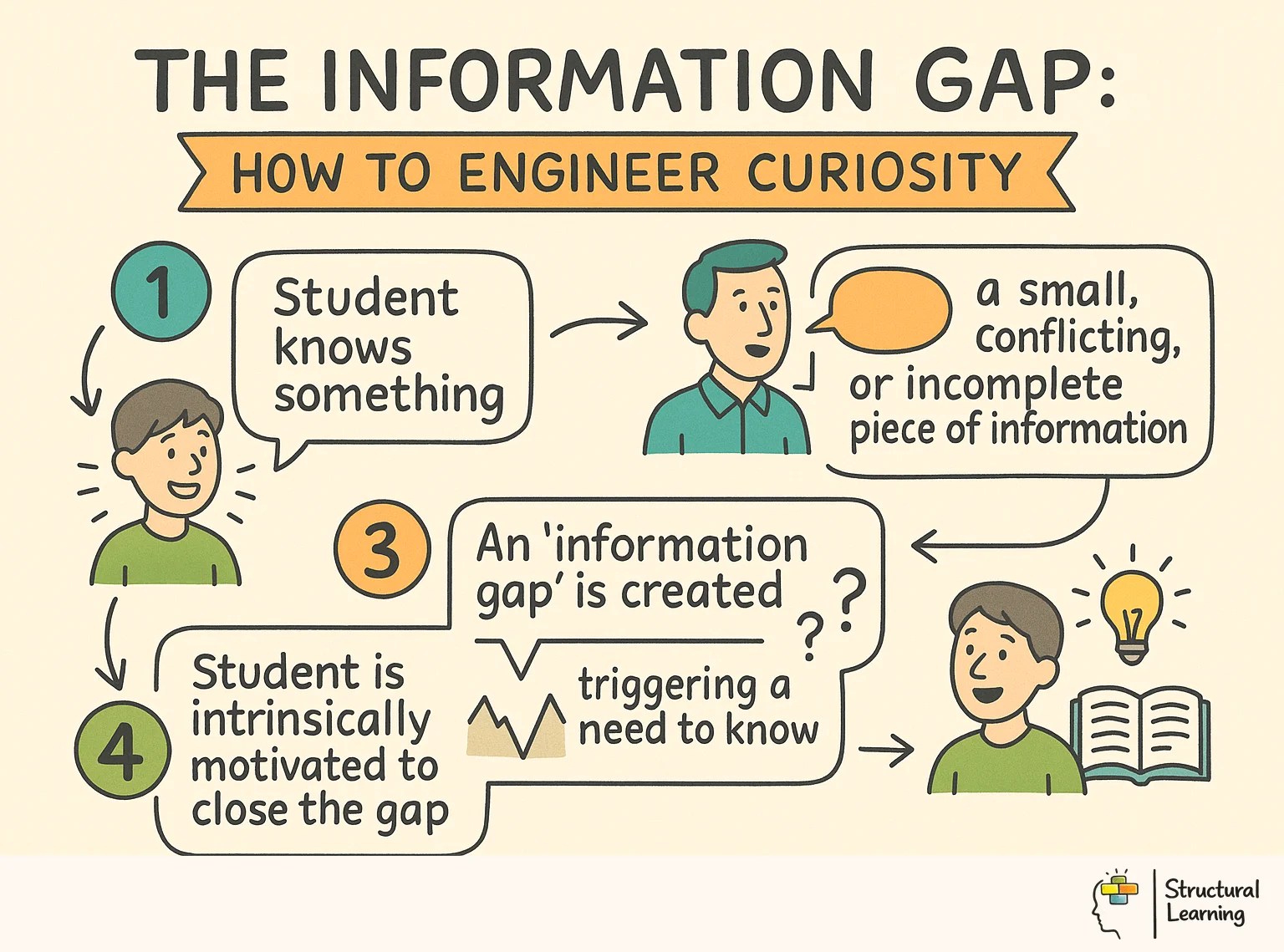

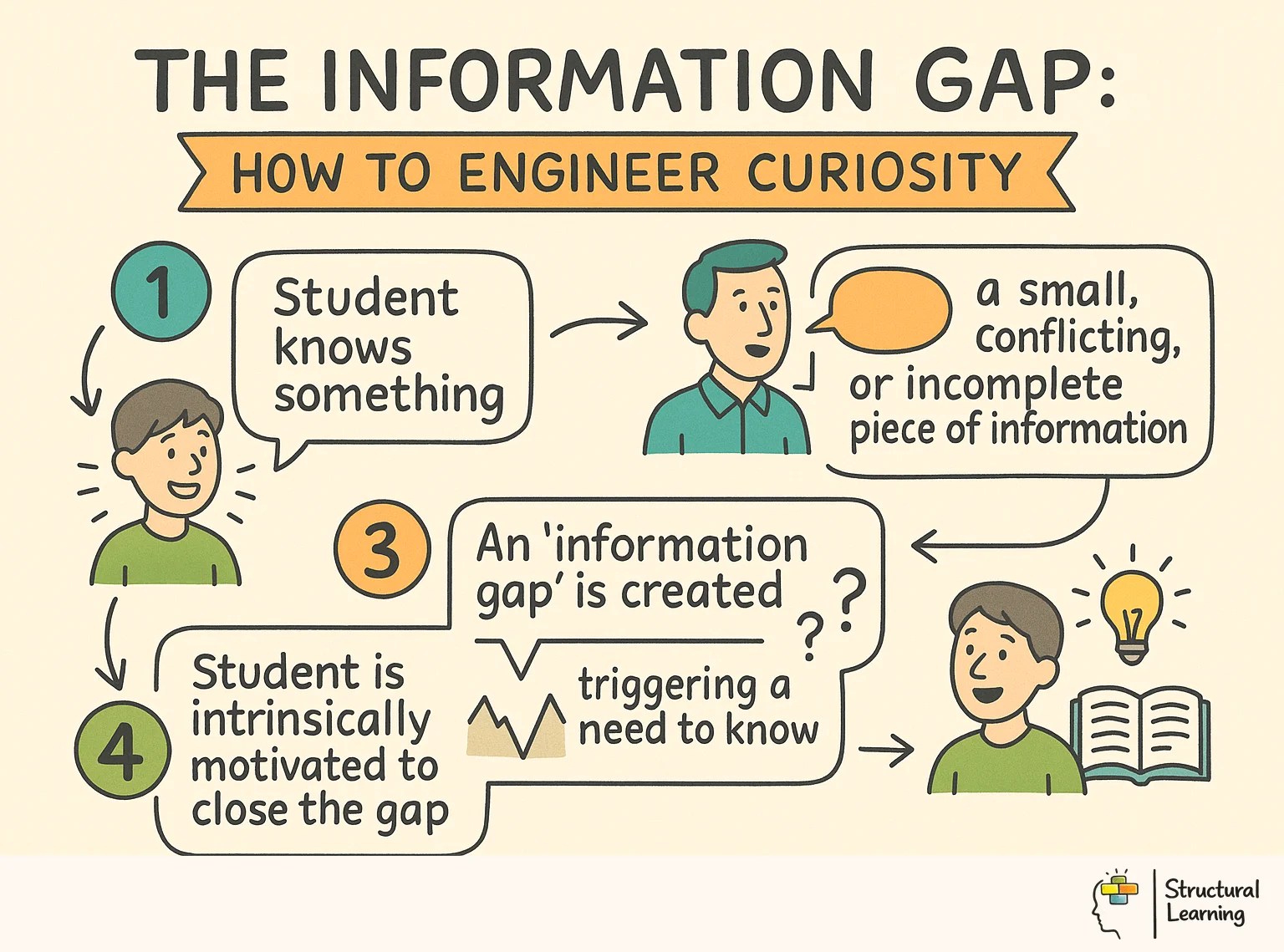

George Loewenstein (1994) proposed that curiosity arises specifically when people are aware of a gap between what they know and what they want to know. Crucially, the gap must be narrow enough to feel solvable. If the gap is too wide, people feel overwhelmed or simply give up. This is called Information Gap Theory, and it explains why some lessons spark curiosity while others fall flat.

Information gaps work most effectively when students have just enough prior knowledge to recognise that a question is worth asking. A Year 3 student who has learned about living things but not about fungi feels a gap when asked, "Are fungi plants?" They want to know. A Year 1 student who has never heard of fungi feels no gap because they do not yet know what they are missing. Similarly, a student who has learned nothing about Shakespeare will not feel a gap when shown two different interpretations of his sonnets; they lack the knowledge scaffolding required to recognise the gap.

The implication is that information gaps must be designed, not assumed. You cannot simply ask an open-ended question and expect curiosity to follow. You must first ensure that students have enough prior knowledge to recognise the gap, and then you must make the gap visible and solvable within a reasonable timeframe. If students work on a question for 30 minutes without progress, the gap ceases to feel solvable, and curiosity turns to frustration (Loewenstein, 1994).

Classroom example: A teacher shows a secondary History class a photograph of the Bayeux Tapestry depicting a comet. Students have already learned that the Normans invaded England in 1066. The teacher asks, "Why would Norman craftspeople include a comet in a scene about invasion?" At this point, most students do not know that Halley's Comet appeared in 1066, but they know enough history to recognise that the detail must matter. A knowledge gap has appeared. The gap is narrow enough to solve: it requires knowing either that comets are significant in history or that dates matter in the tapestry. Over the next lesson, students discover the connection. Curiosity has driven investigation. If the teacher had simply asked, "What do you notice about this tapestry?" without establishing the prior knowledge gap, students might describe colours or figures, but they would not be driven to investigate the comet specifically.

Curiosity changes how the brain processes information. Matthias Gruber and Charan Ranganath (2014) conducted an experiment in which they showed participants trivia questions they had ranked as curiosity-arousing. Using fMRI scanning, they found that when people answered questions they were curious about, activity increased in brain regions associated with memory formation (the hippocampus and midbrain reward areas). The same information presented without curiosity activation did not produce this neural signature.

The practical implication is striking: curiosity does not simply make learning more enjoyable; it makes memory stronger. This is not a minor effect. In Gruber and Ranganath's study, students who had been curious about trivia answers later remembered those answers better, even when tested weeks later. The curiosity state appears to act as a gating mechanism: it flags information as important and strengthens the neural pathways that encode it (Gruber et al., 2014, Neuron).

This has direct classroom relevance. When you rely on routine, it does not matter how carefully you explain it. Students' brains will not allocate memory resources to information that does not activate curiosity or perceived relevance. Conversely, a few minutes spent creating a knowledge gap before teaching a concept can dramatically improve what students remember later. The effort is not wasted on motivation; it is an investment in encoding.

Classroom example: A Year 6 Science teacher could explain photosynthesis by writing the equation on the board and describing the light-dependent and light-independent reactions. Some students will encode the information out of compliance. Alternatively, the teacher could show students a plant growing in a sealed jar with a layer of soil and ask, "If plants need food to grow, and the only food in this jar is soil, how does the plant keep growing?" Students are now aware that they do not understand how plants feed themselves. When the teacher reveals photosynthesis, the explanation lands differently in memory. The knowledge gap has primed the brain to encode the answer.

Curiosity is not linear; more novelty or uncertainty does not produce more curiosity. Berlyne described an inverted U-shape: curiosity rises as events become more novel or surprising, peaks at an optimal level of complexity, and then drops when stimulation becomes too extreme (Berlyne, 1960). If a task is boring, students are not curious; they are indifferent. If a task is completely incomprehensible, students are not curious either; they are frustrated or anxious.

The width of this curve varies by student and by subject. A student with strong prior knowledge in a domain can tolerate more complexity before reaching the "too much" threshold. A student with weak prior knowledge reaches that threshold much sooner. This is why scaffolding is not a remedial add-on; it is a core mechanism for keeping all students within the curiosity window. Without it, some students drop out because the material is too simple, and others drop out because it is too complex (Berlyne, 1960).

The implication is that curiosity-driven teaching requires attention to differentiation. A single-pace lesson will place some students above the optimal stimulation curve and others below it. Both groups disengage. Neither is curious. This is especially important in mixed-ability classes, where the gap between students' prior knowledge can span multiple years.

Classroom example: A secondary Mathematics teacher introduces quadratic equations. Without scaffolding, a student who has not yet mastered expanding brackets and collecting like terms will encounter material beyond their optimal stimulation curve. They will feel confused or give up. At the other end, a student who has already worked with quadratics will find the initial material below their threshold; they will be bored, not curious. The teacher addresses this by using the same core task but varying the complexity of the expressions and the amount of explicit working shown. Curious students are neither bored nor overwhelmed.

Curiosity is not a fixed trait; it is a state that classroom conditions either support or suppress. Edward Deci and Richard Ryan's Self-Determination Theory identifies autonomy, competence, and relatedness as the psychological needs that sustain intrinsic motivation, of which curiosity is a key component. Classrooms that provide autonomy (choice about what or how to investigate), competence (tasks that are solvable with effort), and relatedness (connecting learning to things students care about) sustain curiosity. Those that restrict these elements suppress it (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Five classroom conditions particularly suppress curiosity, often without teachers recognising it:

1. Pre-answering questions before students have time to think. If you ask a question and then supply the answer 10 seconds later, students learn that their job is not to think; it is to listen. Curiosity requires cognitive effort. If you eliminate the need for that effort by answering too quickly, you have signalled that the question was not worth thinking about. Research on Wait Time suggests that increasing silence after a question from 3 seconds to 10 seconds dramatically increases the quality and depth of student responses (Rowe, 1986).

2. Enforcing coverage over understanding. Curricula often require teaching many topics in limited time. When teachers prioritise finishing the topic over allowing students to dwell in genuine uncertainty, curiosity is suppressed. Students learn that the goal is to complete tasks, not to understand. If a teacher moves on from fractions before students have worked through the specific confusions that make fractions difficult (why 1/2 is greater than 1/3, for instance), students will not feel curiosity about fractions later; they will feel anxiety.

3. Grading and ranking in front of peers. Public evaluation of learning, especially when results vary widely across students, activates evaluation anxiety rather than curiosity. Susan Engel's research on how children's curiosity changes across schooling found that children with histories of low performance grades are significantly less likely to ask questions or pursue self-directed investigation (Engel, 2015, The Hungry Mind). They are protecting their self-image, not learning.

4. Providing answers before problems have been posed clearly. If a teacher explains a concept before students have encountered a problem that makes that concept matter, the explanation lands as information to memorise, not as a tool to solve something. This is the inverse of information gap theory. Without the gap, there is no curiosity to direct the learning.

5. Separating learning from agency or choice. When every decision is made by the teacher (what to investigate, how to investigate it, what counts as success), students have no reason to be curious; there is nothing for curiosity to drive. This is distinct from structure and scaffolding, which support curiosity. Autonomy and scaffolding are not opposites; they work together. Students can have genuine choice about how to explore a topic within a carefully designed frame.

Classroom example: In a secondary Geography class, the teacher could say, "Today we are learning about erosion," provide a definition, show a video, and set a worksheet. Or, the teacher could show three photographs of a coastline taken over 50 years apart without comment and ask, "What happened here? Why?" Only after students have formulated questions and attempted their own explanations does the teacher introduce the concept of erosion as a framework for understanding what they have observed. In the first approach, students are compliant. In the second, they are curious.

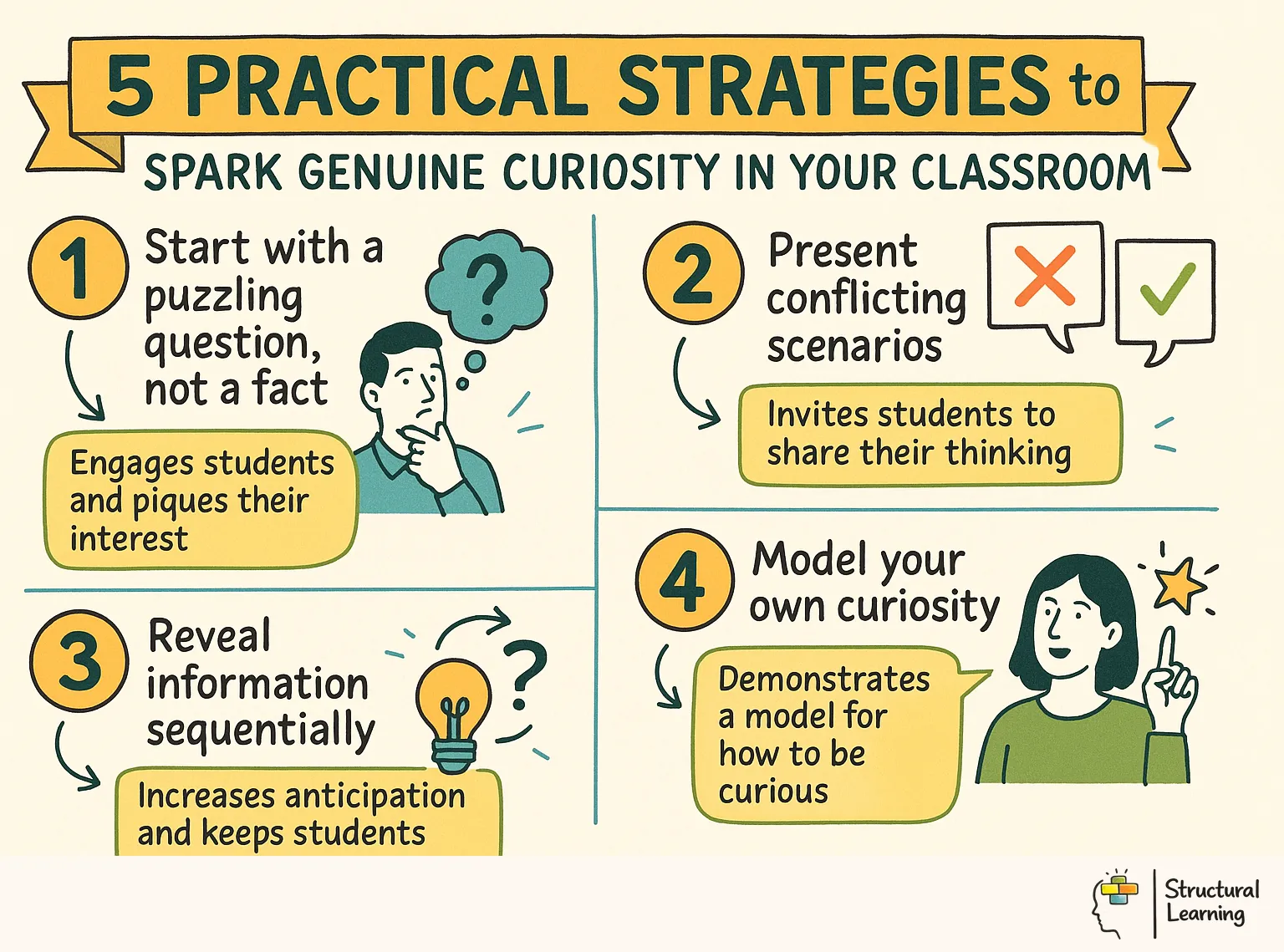

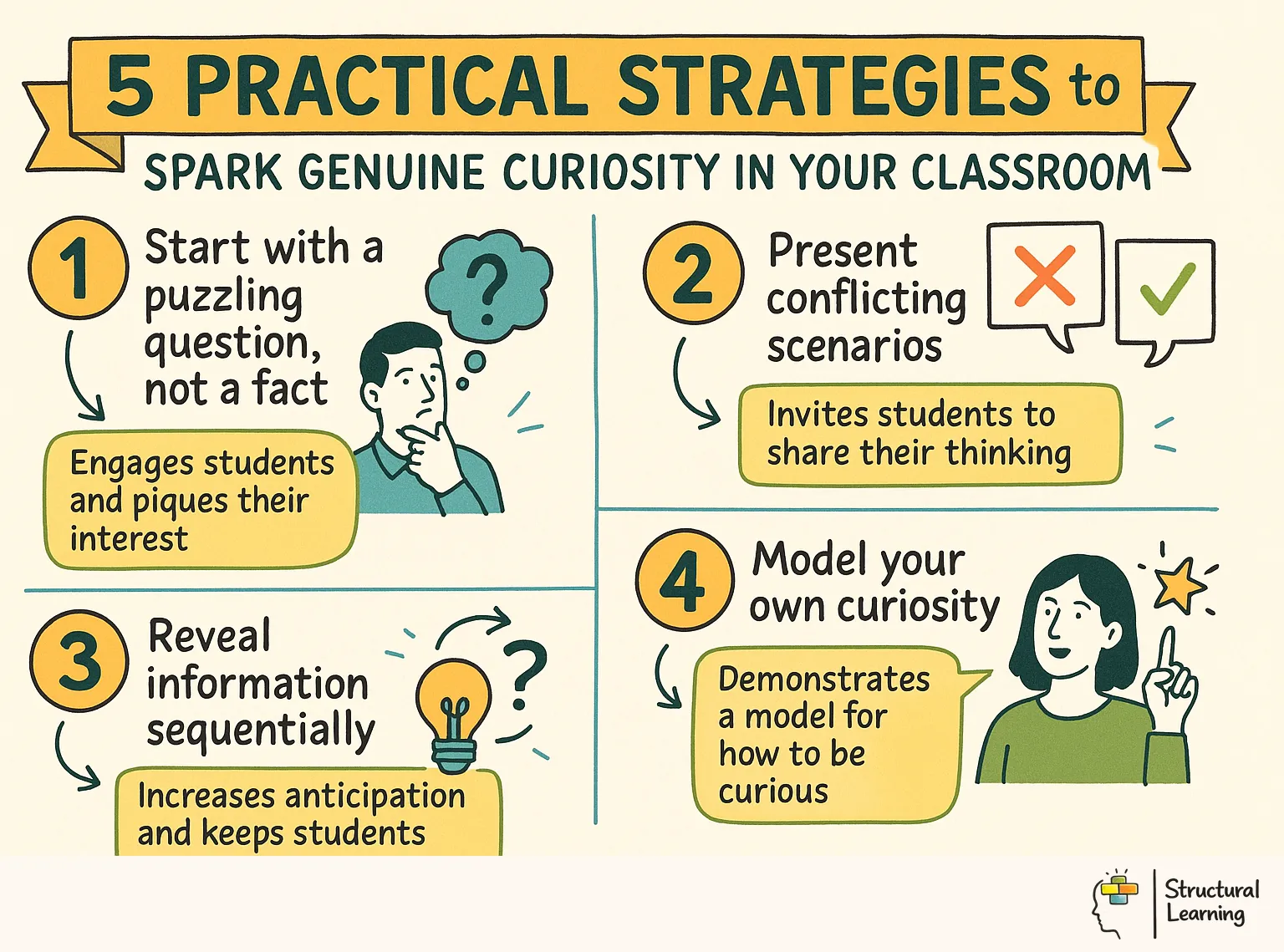

If curiosity is a state that can be cultivated, then it can also be designed into lessons systematically. Rather than hoping that students become curious, you can build structures that reliably trigger epistemic curiosity. Five approaches have strong empirical support:

Mystery tasks. Present a scenario or problem where the answer is not immediately obvious, and the path to the answer requires learning something new. A mystery task is different from an open-ended question because it has a definite answer that students can verify. In a primary Science class, students might be given five liquids of the same colour and asked to identify which is salt water using only the materials provided. The curiosity arises from the gap between the task requirement (identify salt water) and the available information (they all look the same). The resolution requires learning about density or evaporation. The task works because the gap is real, solvable, and verifiable (you can test your prediction).

Jigsaw structures. In a jigsaw activity, each student or group learns one piece of a larger puzzle, then teaches it to others who learned different pieces. The curiosity trigger is asymmetric information: you know something the others do not, and you need to know what they know to understand the whole picture. In a secondary History class, students might research different perspectives on a historical event (Government, Opposition, Foreign observers, common people). Each group becomes expert in one perspective, then teaches the others. Curiosity is triggered by the need to understand the complete picture and by the responsibility to teach others accurately. Jigsaw structures also provide autonomy and a concrete reason for learning (you are teaching others, not just completing a task).

Anomalies and contradictions. Present information that contradicts what students already believe or what they have been taught, but do not immediately explain the contradiction. In a secondary Physics class, a teacher might drop a feather and a hammer inside a vacuum chamber, and they fall at the same rate. Students have learned that heavy objects fall faster. The contradiction creates a gap: how can this be? The curiosity to resolve this anomaly is extremely robust because the contradiction is visibly real. Importantly, the explanation (gravity affects all objects equally; air resistance explains the everyday observation) must come after students have wrestled with the anomaly, not before.

Incomplete information. Give students enough information to start making sense of something, but withhold a crucial detail. In primary Literacy, a teacher might read a story aloud but skip a crucial sentence and ask students to predict what that sentence says based on context. The gap between what they can infer and what they need to verify drives curiosity. Once the sentence is revealed, students are deeply engaged in checking whether their prediction was correct. This works because the gap is narrow and immediately resolvable.

Scaffolded revision. Show students a piece of work (a diagram, a writing sample, an experiment result) that has an error or could be improved, without telling them what is wrong. Ask them to improve it. The curiosity arises from the need to understand why the work is unsatisfactory and how to fix it. This approach also builds metacognition because students must evaluate their own and others' work against criteria.

Classroom example: A secondary English teacher wants students to understand how writers build tension. Instead of explaining narrative techniques, she presents two versions of a scene: one where the protagonist opens a door and finds a birthday party, and one where the same scene is written with delays (describing the hallway, the protagonist's expectations, the sound before the reveal). She asks students to describe the difference in how they felt reading each version. Students immediately recognise that one felt more surprising or powerful, but cannot articulate why. This creates an information gap: they want to know what the writer did differently. Only then does she introduce techniques (foreshadowing, pacing, sensory detail). The techniques are no longer abstract rules; they are tools that explain something students now care about.

Curiosity is not general; it is subject-specific. A student curious about History may have no curiosity about Mathematics, and vice versa. Effective teaching requires hooks that connect to what students already find interesting within each subject domain. This means understanding the natural curiosity triggers within each subject.

In Science, anomalies and unexplained phenomena are powerful. Students are naturally curious about how things work. Effective teachers start with the anomaly (Why do plants need light? Why do magnets attract some metals but not others?), not with the concept. The concept explains the anomaly.

In Mathematics, pattern and puzzle are the natural triggers. Students are curious about why a rule works or whether they can solve a novel problem. A lesson that presents a mathematical pattern and asks students to continue it or explain it taps into epistemic curiosity. Conversely, teaching procedures without showing students the underlying pattern (why does the column method for division work?) leaves no information gap. Students memorise rather than become curious.

In Literacy and Language, mystery and narrative gaps are natural triggers. A teacher might show students an unusual sentence and ask what it suggests about the character or situation, then lead students to discover the techniques that create that effect. Students do not need abstract instruction about metaphor; they need to encounter metaphor as a tool that does something.

In History, contradiction and perspective are powerful triggers. Presenting two accounts of the same event and asking students which is "true" creates a gap: they want to understand why the accounts differ and how to evaluate them. This is more effective than asking students to memorise a sequence of events.

In Geography, prediction and consequence form the natural curiosity trigger. Students predict what happens when a river is dammed or a wetland is drained, then investigate the actual consequences. The gap between prediction and reality drives learning.

In Arts, limitation and constraint are surprisingly powerful triggers. Asking students to convey an emotion using only one colour, or to tell a story using only five objects, creates curiosity about how to solve the constraint. Students care about solving the problem because they have chosen to try.

Classroom example: A secondary Geography teacher wants students to understand watershed boundaries. Rather than describing watersheds and asking students to identify them on a map, the teacher asks students to predict where water will flow on a topographic map. They mark their predictions. Then the teacher reveals actual watershed boundaries. The gap between prediction and reality is the hook that drives learning. Students now care about understanding why water flows the way it does and how topography determines this.

Assessment is not neutral. The culture of assessment in a classroom either supports or suppresses curiosity, especially epistemic curiosity. High-stakes testing, frequent grading, and competition reduce intrinsic curiosity and increase performance anxiety (Deci & Ryan, 1985). This is well established but often ignored in practice.

The mechanism is straightforward: when students are evaluated frequently and publicly, they shift their goal from understanding (epistemic curiosity) to performance (proving competence). These are not compatible mindsets. A student focused on performance is not curious about understanding something difficult; they are motivated to demonstrate what they already know. This is why classrooms with frequent assessment often paradoxically produce compliant but incurious students.

Susan Engel's longitudinal research tracked how children's curiosity evolved between nursery and Year 5. She found that children's rate of question-asking and self-directed investigation declined significantly across this period, with the decline most pronounced in classrooms where evaluation was frequent and public (Engel, 2015). Even children who entered Year 1 as highly curious learners became less likely to ask questions in classrooms that emphasised grading and performance.

This does not mean abandoning formative assessment. Assessment that provides information to support learning (formative assessment) can support curiosity if it is formative in practice, not just name. Formative assessment means using information from assessment to adjust teaching, not grading student work publicly or using it to rank students. The difference is whether assessment feels like "we are checking your understanding so we can help you" or "we are checking whether you are smart."

One practical approach is to use assessment without grades. When a teacher marks a student's work and writes feedback but does not assign a grade, the focus shifts from performance to learning. The student is more likely to be curious about understanding the feedback. This is slower than grading (it is harder to assign a grade than to provide detailed feedback), which is precisely why it is effective. It signals that understanding matters more than speed.

Classroom example: Two secondary Mathematics classes study retrieval practice quizzes. In the first class, quizzes are graded and contribute to the student's final mark. Students are anxious about performance and focus on memorising answers. In the second class, quizzes are used to identify gaps in understanding, but students receive only feedback, not grades. Questions that students answered incorrectly are revisited in lessons, and students are explicitly thanked for revealing gaps. Over time, students in the second class ask more questions and are more willing to attempt difficult problems because the quiz is a tool for learning, not a judgment. They are more curious.

Curiosity is often measured through questionnaires or self-report, which are indirect and unreliable with younger students. If you want to know whether your classroom conditions support curiosity, look for observable behaviours. Todd Kashdan's Curiosity and Exploration Inventory identifies behaviours that reflect genuine curiosity: asking questions, seeking novel information, and persisting through difficulty. These are observable.

Question-asking. Track how many genuine (not procedural) questions students ask during a lesson. A genuine question seeks to understand something; a procedural question asks for permission or clarification about a task. In a curious classroom, students ask more genuine questions. This is simple to count and provides immediate feedback on whether your lesson structure is creating information gaps.

Persistence on difficult tasks. Students who are curious continue working on a task even after initial attempts fail. Students who are not curious quickly ask for help or give up. Time spent on an unsolved problem before asking for help is a proxy for curiosity. Note that this is distinct from productive struggle. A student struggling productively is engaged but may not be curious. A curious student is struggling with purpose; they are trying to resolve a gap in understanding.

Elaboration and explanation. When students explain their thinking to a peer or to you, and they go beyond what was required, they are likely curious. A student who says, "I think it is this because..." and then adds extra reasoning is trying to understand, not just comply. Notice the difference between minimal explanations (exactly what was asked) and elaborated explanations (more than asked, unexpected connections).

Self-directed investigation. Do students pursue questions that were not assigned? Do they choose to read about the topic beyond what is required? Do they ask if they can investigate a related question? In a curious classroom, some independent inquiry happens without being prompted. This is rare and precious. When it happens, note what conditions triggered it.

Topic choice and effort. When students have choice about what to investigate within a topic, do they choose topics that are easy or familiar, or do they choose topics that are unfamiliar or challenging? Choice of difficult topics suggests curiosity. Choice of only easy or familiar topics suggests students are motivated by performance, not understanding.

Reduced external motivation. If a classroom is supporting curiosity, students continue working and asking questions even when external rewards (grades, praise, prizes) are removed. A student who works hard only for a grade is not curious; they are externally motivated. A student who works hard because they want to understand is curious. You can test this by noticing whether students' engagement changes when you remove grading or public recognition from a task.

Classroom example: A secondary Science teacher observed that in her lessons on ecosystems, some students asked questions like, "How do the plants know how much water to take up?" and "What would happen if we removed all the herbivores?" and continued investigating even when initial research did not yield answers. She noticed that these questions emerged after she had spent time in previous lessons creating concrete anomalies (showing plants in different soil types growing at different rates; showing how removing a species affected others in a terrarium). The information gaps triggered by anomalies had made students curious. In contrast, lessons where she had presented factual information without anomalies produced fewer genuine questions. By observing question-asking, she had identified which teaching approaches supported curiosity.

Curiosity is not something that students either have or lack. It is a state that teaching practices and classroom conditions reliably trigger or suppress. You can immediately begin designing information gaps into your lessons, building jigsaw structures that create asymmetric information, introducing anomalies before explanations, and observing whether your students are asking genuine questions. The research is clear: curiosity changes how brains encode information, but only if you create the conditions that allow it to emerge. Choose one subject or one unit, and redesign it around a central anomaly, mystery, or contradiction. Then track what happens to your students' questions and engagement. If you are a sceptical teacher, let the data decide whether structured curiosity is worth your effort.

Curiosity is not optional in education. It is the engine that drives voluntary effort, enables memory formation, and sustains learning when tasks become difficult. Yet classroom conditions often suppress curiosity rather than nurture it, and teachers frequently confuse curiosity with interest or novelty. This article examines the cognitive science of curiosity, provides practical strategies to trigger it systematically, and offers tools to observe whether your students are genuinely curious or merely compliant.

Curiosity is not one thing. Daniel Berlyne's foundational distinction between epistemic and perceptual curiosity (1960) remains the most useful framework for teachers. Epistemic curiosity is the desire to know; it arises when you encounter a gap between what you know and what you want to know. Perceptual curiosity, by contrast, is the desire to perceive something novel or complex; it attracts attention but does not necessarily drive learning.

In your classroom, these operate differently. When a Year 5 student is puzzled by why salt dissolves in water but sand does not, they are in a state of epistemic curiosity. They want to understand. When the same student is momentarily distracted by a colourful poster on the wall, that is perceptual curiosity. It grabs attention but fades quickly. Diversive curiosity is a third form: the desire for novel experience rather than the resolution of a specific knowledge gap. It is what drives students to open a book about medieval castles when they have no learning target related to castles. In classrooms that prioritise motivation above all else, diversive curiosity is often mistaken for engagement (Berlyne, 1960).

Epistemic curiosity is what you should cultivate. It is relatively stable, leads to deeper processing, and improves retention. Here is a practical distinction: if your student wants to know the answer to a question, they are epistemically curious. If they are simply attracted to something shiny or unexpected, they are experiencing perceptual curiosity, which is fleeting.

Classroom example: In a secondary English class, the teacher shows two opening lines: "The sky was blue." and "The sky dripped rust." Without explanation, students ask which is "better" and why the second one breaks the rule. That is epistemic curiosity. They want to understand. If the teacher had simply shown a dramatic image of a rust-coloured sunset and asked students to write about it, students might produce creative work, but they would not necessarily be curious about how and why writers make deliberate choices. The difference is whether students are trying to resolve a gap in understanding, not whether they are engaged.

George Loewenstein (1994) proposed that curiosity arises specifically when people are aware of a gap between what they know and what they want to know. Crucially, the gap must be narrow enough to feel solvable. If the gap is too wide, people feel overwhelmed or simply give up. This is called Information Gap Theory, and it explains why some lessons spark curiosity while others fall flat.

Information gaps work most effectively when students have just enough prior knowledge to recognise that a question is worth asking. A Year 3 student who has learned about living things but not about fungi feels a gap when asked, "Are fungi plants?" They want to know. A Year 1 student who has never heard of fungi feels no gap because they do not yet know what they are missing. Similarly, a student who has learned nothing about Shakespeare will not feel a gap when shown two different interpretations of his sonnets; they lack the knowledge scaffolding required to recognise the gap.

The implication is that information gaps must be designed, not assumed. You cannot simply ask an open-ended question and expect curiosity to follow. You must first ensure that students have enough prior knowledge to recognise the gap, and then you must make the gap visible and solvable within a reasonable timeframe. If students work on a question for 30 minutes without progress, the gap ceases to feel solvable, and curiosity turns to frustration (Loewenstein, 1994).

Classroom example: A teacher shows a secondary History class a photograph of the Bayeux Tapestry depicting a comet. Students have already learned that the Normans invaded England in 1066. The teacher asks, "Why would Norman craftspeople include a comet in a scene about invasion?" At this point, most students do not know that Halley's Comet appeared in 1066, but they know enough history to recognise that the detail must matter. A knowledge gap has appeared. The gap is narrow enough to solve: it requires knowing either that comets are significant in history or that dates matter in the tapestry. Over the next lesson, students discover the connection. Curiosity has driven investigation. If the teacher had simply asked, "What do you notice about this tapestry?" without establishing the prior knowledge gap, students might describe colours or figures, but they would not be driven to investigate the comet specifically.

Curiosity changes how the brain processes information. Matthias Gruber and Charan Ranganath (2014) conducted an experiment in which they showed participants trivia questions they had ranked as curiosity-arousing. Using fMRI scanning, they found that when people answered questions they were curious about, activity increased in brain regions associated with memory formation (the hippocampus and midbrain reward areas). The same information presented without curiosity activation did not produce this neural signature.

The practical implication is striking: curiosity does not simply make learning more enjoyable; it makes memory stronger. This is not a minor effect. In Gruber and Ranganath's study, students who had been curious about trivia answers later remembered those answers better, even when tested weeks later. The curiosity state appears to act as a gating mechanism: it flags information as important and strengthens the neural pathways that encode it (Gruber et al., 2014, Neuron).

This has direct classroom relevance. When you rely on routine, it does not matter how carefully you explain it. Students' brains will not allocate memory resources to information that does not activate curiosity or perceived relevance. Conversely, a few minutes spent creating a knowledge gap before teaching a concept can dramatically improve what students remember later. The effort is not wasted on motivation; it is an investment in encoding.

Classroom example: A Year 6 Science teacher could explain photosynthesis by writing the equation on the board and describing the light-dependent and light-independent reactions. Some students will encode the information out of compliance. Alternatively, the teacher could show students a plant growing in a sealed jar with a layer of soil and ask, "If plants need food to grow, and the only food in this jar is soil, how does the plant keep growing?" Students are now aware that they do not understand how plants feed themselves. When the teacher reveals photosynthesis, the explanation lands differently in memory. The knowledge gap has primed the brain to encode the answer.

Curiosity is not linear; more novelty or uncertainty does not produce more curiosity. Berlyne described an inverted U-shape: curiosity rises as events become more novel or surprising, peaks at an optimal level of complexity, and then drops when stimulation becomes too extreme (Berlyne, 1960). If a task is boring, students are not curious; they are indifferent. If a task is completely incomprehensible, students are not curious either; they are frustrated or anxious.

The width of this curve varies by student and by subject. A student with strong prior knowledge in a domain can tolerate more complexity before reaching the "too much" threshold. A student with weak prior knowledge reaches that threshold much sooner. This is why scaffolding is not a remedial add-on; it is a core mechanism for keeping all students within the curiosity window. Without it, some students drop out because the material is too simple, and others drop out because it is too complex (Berlyne, 1960).

The implication is that curiosity-driven teaching requires attention to differentiation. A single-pace lesson will place some students above the optimal stimulation curve and others below it. Both groups disengage. Neither is curious. This is especially important in mixed-ability classes, where the gap between students' prior knowledge can span multiple years.

Classroom example: A secondary Mathematics teacher introduces quadratic equations. Without scaffolding, a student who has not yet mastered expanding brackets and collecting like terms will encounter material beyond their optimal stimulation curve. They will feel confused or give up. At the other end, a student who has already worked with quadratics will find the initial material below their threshold; they will be bored, not curious. The teacher addresses this by using the same core task but varying the complexity of the expressions and the amount of explicit working shown. Curious students are neither bored nor overwhelmed.

Curiosity is not a fixed trait; it is a state that classroom conditions either support or suppress. Edward Deci and Richard Ryan's Self-Determination Theory identifies autonomy, competence, and relatedness as the psychological needs that sustain intrinsic motivation, of which curiosity is a key component. Classrooms that provide autonomy (choice about what or how to investigate), competence (tasks that are solvable with effort), and relatedness (connecting learning to things students care about) sustain curiosity. Those that restrict these elements suppress it (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Five classroom conditions particularly suppress curiosity, often without teachers recognising it:

1. Pre-answering questions before students have time to think. If you ask a question and then supply the answer 10 seconds later, students learn that their job is not to think; it is to listen. Curiosity requires cognitive effort. If you eliminate the need for that effort by answering too quickly, you have signalled that the question was not worth thinking about. Research on Wait Time suggests that increasing silence after a question from 3 seconds to 10 seconds dramatically increases the quality and depth of student responses (Rowe, 1986).

2. Enforcing coverage over understanding. Curricula often require teaching many topics in limited time. When teachers prioritise finishing the topic over allowing students to dwell in genuine uncertainty, curiosity is suppressed. Students learn that the goal is to complete tasks, not to understand. If a teacher moves on from fractions before students have worked through the specific confusions that make fractions difficult (why 1/2 is greater than 1/3, for instance), students will not feel curiosity about fractions later; they will feel anxiety.

3. Grading and ranking in front of peers. Public evaluation of learning, especially when results vary widely across students, activates evaluation anxiety rather than curiosity. Susan Engel's research on how children's curiosity changes across schooling found that children with histories of low performance grades are significantly less likely to ask questions or pursue self-directed investigation (Engel, 2015, The Hungry Mind). They are protecting their self-image, not learning.

4. Providing answers before problems have been posed clearly. If a teacher explains a concept before students have encountered a problem that makes that concept matter, the explanation lands as information to memorise, not as a tool to solve something. This is the inverse of information gap theory. Without the gap, there is no curiosity to direct the learning.

5. Separating learning from agency or choice. When every decision is made by the teacher (what to investigate, how to investigate it, what counts as success), students have no reason to be curious; there is nothing for curiosity to drive. This is distinct from structure and scaffolding, which support curiosity. Autonomy and scaffolding are not opposites; they work together. Students can have genuine choice about how to explore a topic within a carefully designed frame.

Classroom example: In a secondary Geography class, the teacher could say, "Today we are learning about erosion," provide a definition, show a video, and set a worksheet. Or, the teacher could show three photographs of a coastline taken over 50 years apart without comment and ask, "What happened here? Why?" Only after students have formulated questions and attempted their own explanations does the teacher introduce the concept of erosion as a framework for understanding what they have observed. In the first approach, students are compliant. In the second, they are curious.

If curiosity is a state that can be cultivated, then it can also be designed into lessons systematically. Rather than hoping that students become curious, you can build structures that reliably trigger epistemic curiosity. Five approaches have strong empirical support:

Mystery tasks. Present a scenario or problem where the answer is not immediately obvious, and the path to the answer requires learning something new. A mystery task is different from an open-ended question because it has a definite answer that students can verify. In a primary Science class, students might be given five liquids of the same colour and asked to identify which is salt water using only the materials provided. The curiosity arises from the gap between the task requirement (identify salt water) and the available information (they all look the same). The resolution requires learning about density or evaporation. The task works because the gap is real, solvable, and verifiable (you can test your prediction).

Jigsaw structures. In a jigsaw activity, each student or group learns one piece of a larger puzzle, then teaches it to others who learned different pieces. The curiosity trigger is asymmetric information: you know something the others do not, and you need to know what they know to understand the whole picture. In a secondary History class, students might research different perspectives on a historical event (Government, Opposition, Foreign observers, common people). Each group becomes expert in one perspective, then teaches the others. Curiosity is triggered by the need to understand the complete picture and by the responsibility to teach others accurately. Jigsaw structures also provide autonomy and a concrete reason for learning (you are teaching others, not just completing a task).

Anomalies and contradictions. Present information that contradicts what students already believe or what they have been taught, but do not immediately explain the contradiction. In a secondary Physics class, a teacher might drop a feather and a hammer inside a vacuum chamber, and they fall at the same rate. Students have learned that heavy objects fall faster. The contradiction creates a gap: how can this be? The curiosity to resolve this anomaly is extremely robust because the contradiction is visibly real. Importantly, the explanation (gravity affects all objects equally; air resistance explains the everyday observation) must come after students have wrestled with the anomaly, not before.

Incomplete information. Give students enough information to start making sense of something, but withhold a crucial detail. In primary Literacy, a teacher might read a story aloud but skip a crucial sentence and ask students to predict what that sentence says based on context. The gap between what they can infer and what they need to verify drives curiosity. Once the sentence is revealed, students are deeply engaged in checking whether their prediction was correct. This works because the gap is narrow and immediately resolvable.

Scaffolded revision. Show students a piece of work (a diagram, a writing sample, an experiment result) that has an error or could be improved, without telling them what is wrong. Ask them to improve it. The curiosity arises from the need to understand why the work is unsatisfactory and how to fix it. This approach also builds metacognition because students must evaluate their own and others' work against criteria.

Classroom example: A secondary English teacher wants students to understand how writers build tension. Instead of explaining narrative techniques, she presents two versions of a scene: one where the protagonist opens a door and finds a birthday party, and one where the same scene is written with delays (describing the hallway, the protagonist's expectations, the sound before the reveal). She asks students to describe the difference in how they felt reading each version. Students immediately recognise that one felt more surprising or powerful, but cannot articulate why. This creates an information gap: they want to know what the writer did differently. Only then does she introduce techniques (foreshadowing, pacing, sensory detail). The techniques are no longer abstract rules; they are tools that explain something students now care about.

Curiosity is not general; it is subject-specific. A student curious about History may have no curiosity about Mathematics, and vice versa. Effective teaching requires hooks that connect to what students already find interesting within each subject domain. This means understanding the natural curiosity triggers within each subject.

In Science, anomalies and unexplained phenomena are powerful. Students are naturally curious about how things work. Effective teachers start with the anomaly (Why do plants need light? Why do magnets attract some metals but not others?), not with the concept. The concept explains the anomaly.

In Mathematics, pattern and puzzle are the natural triggers. Students are curious about why a rule works or whether they can solve a novel problem. A lesson that presents a mathematical pattern and asks students to continue it or explain it taps into epistemic curiosity. Conversely, teaching procedures without showing students the underlying pattern (why does the column method for division work?) leaves no information gap. Students memorise rather than become curious.

In Literacy and Language, mystery and narrative gaps are natural triggers. A teacher might show students an unusual sentence and ask what it suggests about the character or situation, then lead students to discover the techniques that create that effect. Students do not need abstract instruction about metaphor; they need to encounter metaphor as a tool that does something.

In History, contradiction and perspective are powerful triggers. Presenting two accounts of the same event and asking students which is "true" creates a gap: they want to understand why the accounts differ and how to evaluate them. This is more effective than asking students to memorise a sequence of events.

In Geography, prediction and consequence form the natural curiosity trigger. Students predict what happens when a river is dammed or a wetland is drained, then investigate the actual consequences. The gap between prediction and reality drives learning.

In Arts, limitation and constraint are surprisingly powerful triggers. Asking students to convey an emotion using only one colour, or to tell a story using only five objects, creates curiosity about how to solve the constraint. Students care about solving the problem because they have chosen to try.

Classroom example: A secondary Geography teacher wants students to understand watershed boundaries. Rather than describing watersheds and asking students to identify them on a map, the teacher asks students to predict where water will flow on a topographic map. They mark their predictions. Then the teacher reveals actual watershed boundaries. The gap between prediction and reality is the hook that drives learning. Students now care about understanding why water flows the way it does and how topography determines this.

Assessment is not neutral. The culture of assessment in a classroom either supports or suppresses curiosity, especially epistemic curiosity. High-stakes testing, frequent grading, and competition reduce intrinsic curiosity and increase performance anxiety (Deci & Ryan, 1985). This is well established but often ignored in practice.

The mechanism is straightforward: when students are evaluated frequently and publicly, they shift their goal from understanding (epistemic curiosity) to performance (proving competence). These are not compatible mindsets. A student focused on performance is not curious about understanding something difficult; they are motivated to demonstrate what they already know. This is why classrooms with frequent assessment often paradoxically produce compliant but incurious students.

Susan Engel's longitudinal research tracked how children's curiosity evolved between nursery and Year 5. She found that children's rate of question-asking and self-directed investigation declined significantly across this period, with the decline most pronounced in classrooms where evaluation was frequent and public (Engel, 2015). Even children who entered Year 1 as highly curious learners became less likely to ask questions in classrooms that emphasised grading and performance.

This does not mean abandoning formative assessment. Assessment that provides information to support learning (formative assessment) can support curiosity if it is formative in practice, not just name. Formative assessment means using information from assessment to adjust teaching, not grading student work publicly or using it to rank students. The difference is whether assessment feels like "we are checking your understanding so we can help you" or "we are checking whether you are smart."

One practical approach is to use assessment without grades. When a teacher marks a student's work and writes feedback but does not assign a grade, the focus shifts from performance to learning. The student is more likely to be curious about understanding the feedback. This is slower than grading (it is harder to assign a grade than to provide detailed feedback), which is precisely why it is effective. It signals that understanding matters more than speed.

Classroom example: Two secondary Mathematics classes study retrieval practice quizzes. In the first class, quizzes are graded and contribute to the student's final mark. Students are anxious about performance and focus on memorising answers. In the second class, quizzes are used to identify gaps in understanding, but students receive only feedback, not grades. Questions that students answered incorrectly are revisited in lessons, and students are explicitly thanked for revealing gaps. Over time, students in the second class ask more questions and are more willing to attempt difficult problems because the quiz is a tool for learning, not a judgment. They are more curious.

Curiosity is often measured through questionnaires or self-report, which are indirect and unreliable with younger students. If you want to know whether your classroom conditions support curiosity, look for observable behaviours. Todd Kashdan's Curiosity and Exploration Inventory identifies behaviours that reflect genuine curiosity: asking questions, seeking novel information, and persisting through difficulty. These are observable.

Question-asking. Track how many genuine (not procedural) questions students ask during a lesson. A genuine question seeks to understand something; a procedural question asks for permission or clarification about a task. In a curious classroom, students ask more genuine questions. This is simple to count and provides immediate feedback on whether your lesson structure is creating information gaps.

Persistence on difficult tasks. Students who are curious continue working on a task even after initial attempts fail. Students who are not curious quickly ask for help or give up. Time spent on an unsolved problem before asking for help is a proxy for curiosity. Note that this is distinct from productive struggle. A student struggling productively is engaged but may not be curious. A curious student is struggling with purpose; they are trying to resolve a gap in understanding.

Elaboration and explanation. When students explain their thinking to a peer or to you, and they go beyond what was required, they are likely curious. A student who says, "I think it is this because..." and then adds extra reasoning is trying to understand, not just comply. Notice the difference between minimal explanations (exactly what was asked) and elaborated explanations (more than asked, unexpected connections).

Self-directed investigation. Do students pursue questions that were not assigned? Do they choose to read about the topic beyond what is required? Do they ask if they can investigate a related question? In a curious classroom, some independent inquiry happens without being prompted. This is rare and precious. When it happens, note what conditions triggered it.

Topic choice and effort. When students have choice about what to investigate within a topic, do they choose topics that are easy or familiar, or do they choose topics that are unfamiliar or challenging? Choice of difficult topics suggests curiosity. Choice of only easy or familiar topics suggests students are motivated by performance, not understanding.

Reduced external motivation. If a classroom is supporting curiosity, students continue working and asking questions even when external rewards (grades, praise, prizes) are removed. A student who works hard only for a grade is not curious; they are externally motivated. A student who works hard because they want to understand is curious. You can test this by noticing whether students' engagement changes when you remove grading or public recognition from a task.

Classroom example: A secondary Science teacher observed that in her lessons on ecosystems, some students asked questions like, "How do the plants know how much water to take up?" and "What would happen if we removed all the herbivores?" and continued investigating even when initial research did not yield answers. She noticed that these questions emerged after she had spent time in previous lessons creating concrete anomalies (showing plants in different soil types growing at different rates; showing how removing a species affected others in a terrarium). The information gaps triggered by anomalies had made students curious. In contrast, lessons where she had presented factual information without anomalies produced fewer genuine questions. By observing question-asking, she had identified which teaching approaches supported curiosity.

Curiosity is not something that students either have or lack. It is a state that teaching practices and classroom conditions reliably trigger or suppress. You can immediately begin designing information gaps into your lessons, building jigsaw structures that create asymmetric information, introducing anomalies before explanations, and observing whether your students are asking genuine questions. The research is clear: curiosity changes how brains encode information, but only if you create the conditions that allow it to emerge. Choose one subject or one unit, and redesign it around a central anomaly, mystery, or contradiction. Then track what happens to your students' questions and engagement. If you are a sceptical teacher, let the data decide whether structured curiosity is worth your effort.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Organization","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/#org","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/5b69a01ba2e40996a5e055f4_structural-learning-logo.png"}},{"@type":"Person","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paul-main/#person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paul-main","jobTitle":"Founder","affiliation":{"@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/#org"}},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/curiosity-driven-learning-every-teacher#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Curiosity-Driven Learning: What Every Teacher Needs to Know","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/curiosity-driven-learning-every-teacher"}]},{"@type":"BlogPosting","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/curiosity-driven-learning-every-teacher#article","headline":"Curiosity-Driven Learning: What Every Teacher Needs to Know","description":"","author":{"@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paul-main/#person"},"publisher":{"@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/#org"},"datePublished":"2026-02-19","dateModified":"2026-02-19","inLanguage":"en-GB"}]}